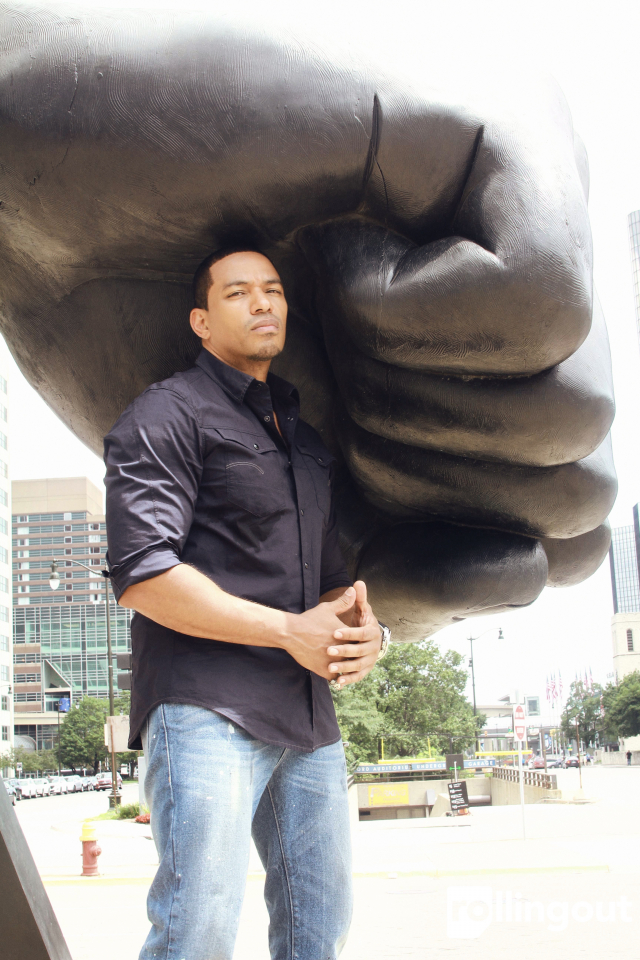

The Black Fist represents the strength of Detroit. Known as the “Monument to Joe Louis” and located in the epicenter of Detroit, the Black Fist serves as a symbol for a fighting city that always finds a way to persevere. It has grappled with its history of racial strife and segregation, a financial crisis, political scandals, and a mass exodus of its residents.

Ironically, while Detroit is the very city that inspired the legacy of Motown, it too stewed the racial conditions that led to the 1967 rebellion. Still, similar to the great Detroit pugilist Joe Louis, through all of these fights and contradictions, Detroit always has a fighter’s chance.

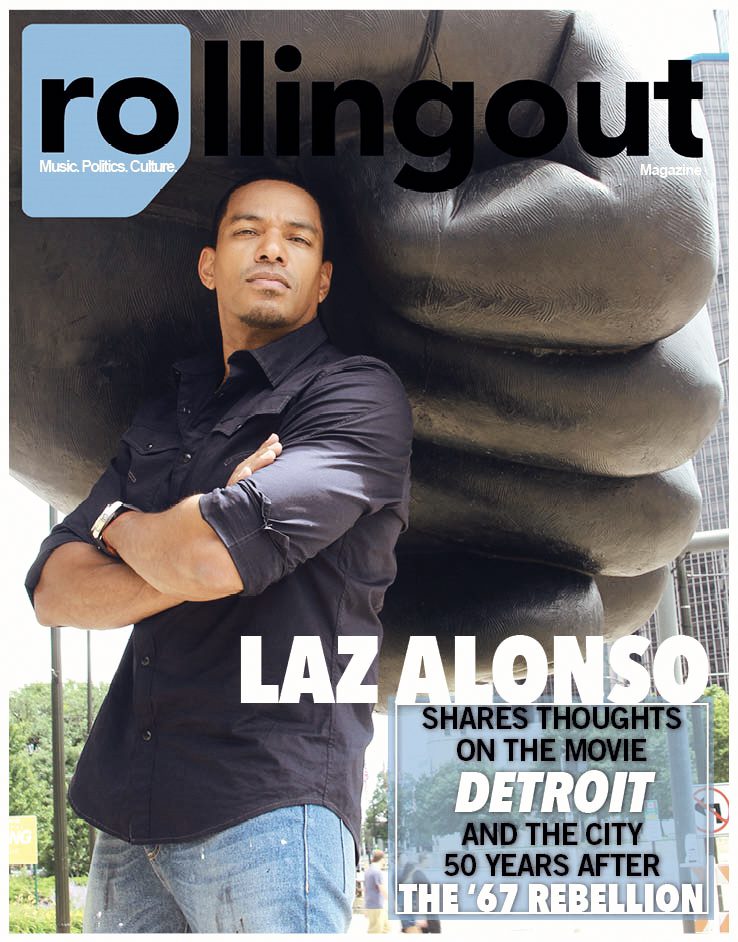

On a warm afternoon in July, the Black Fist served as the backdrop for a photo shoot with actor Laz Alonso. Alonso portrays Congressman John Conyers in the new film Detroit. For decades, Conyers has remained on the front lines when it comes to civil and human rights for the citizens of Detroit. During the Rebellion of 1967, Conyers was a major voice in the community who worked to redirect the frustrations of the citizens in Detroit.

“I actually studied a lot of tape on him, studied a lot of interviews,” Alonso said about preparing himself for the role. “I tried to go back as far and as close to 1967 as possible. That was 50 years ago. But a lot of his words, his diction, his speed in which he speaks, his rhythm, I tried to capture that. And then we have to elevate [his speech] to the point of being in an intense situation and an intense environment — the way to speak now and the way you speak with 5K people around you about to stand up and possibly get violent is different. So, I had to take creative liberty to also take what I learned and then apply it to an intense environment. I hope that he is happy with my work.”

The movie Detroit highlights an incident at the Algiers Motel that took place on July 25 and 26 during the 1967 rebellion. Three Black teens were killed by White police officers during a night of brutality and terror that proved to be an act of racial violence.

“[Director] Kathryn Bigelow [Zero Dark Thirty, The Hurt Locker] put a small group of actors together and we came together to do the table read and bring the characters to life,” Alonso said. “So when we did that, I read about five or six different characters in the film so that they could just hear the characters voices and hear it come to life. I was not familiar with this particular rebellion. We’ve chosen to use the term rebellion more so than riot because riot implies criminal activity and this wasn’t necessarily something that should be criminalized. It was more of a rebellion — people speaking out against injustice and a situation that should just not have happened.”

But while the film captures the horrors of racism, it doesn’t tell the entire story of how the 1967 uprising transpired and the racial injustice that beget violence. I recently visited the west side of Detroit where the rebellion took place 50 years ago. Older residents and historians who still reside in the community spoke to me about what really led to the unrest.

“It’s really hard to talk about the riots in 1967 and start in 1967,” Detroit native and historian Jamon Jordan told me. “For decades prior to 1967, African Americans had been living in a Detroit that was highly constricted by racism. This racism showed up in various numbers of forms, but primarily in housing discrimination and property discrimination. African Americans could not own businesses and could not live in parts of the city, which meant that people who owned homes in that area had signed covenants stating they would not sell or lease to a Black person when they moved … So you have that and then later when African Americans could get their own school, the schools were segregated and then they had zoning rules to keep African Americans in specific schools and out of predominantly white schools. The resources that go into predominantly African American schools are inferior to the resources that go into predominantly White schools. … And another issue was police brutality. There was a unit in the city of Detroit started in 1950 known as the Big Four. The Big Four was one uniform officer and three plainclothes officers in an unmarked unit and they were notoriously brutal to African Americans. They would drive the streets and they would say, ‘Give up the corner’ and you had to get off the corner and go home. If you didn’t get up fast enough, you would be beaten. Along with that, you had a 95 percent white police force in a predominantly Black city.”

The precursors to the 1967 rebellion in Detroit were examples of what can occur when a group of people is stifled due to systemic and overt racism. It remains a problem 50 years after the rebellion. According to a study done by the Brookings Institution, Detroit has the highest rate of concentrated poverty among the top 25 metro areas in the U.S. by population. It’s a city where you can see rows of abandoned and dilapidated homes that are only a few blocks away from manicured lawns and mini-mansions in the historic neighborhood of Boston-Edison. It’s a city where the middle class is mostly depleted and there is an even wider divide between rich and poor.

There is an attempt to rebuild Detroit, but Black residents could be absent from the city’s plans. Billionaire Dan Gilbert recently caught flack because of an advertisement that stated, “See Detroit Like We Do,” that only featured White people. In a city that remains 80 percent Black, it appeared to be a promotion for gentrification. Gilbert apologized for the ad, but the Freudian slip should not be ignored.

“The story in Detroit is a story that we see all over the country,” Alonso said. “A lot of local residents are displaced. Although you see a lot of community building, it’s not inclusive of the original community of that city and that’s a struggle that’s nationwide. We are all Detroit. I think that [gentrification] is definitely a subject that is being addressed. It’s an ongoing topic of conversation. I just saw somewhere that they were trying to rename Harlem, “SoHa” – South Harlem. And the residents were like, ‘Nah, this is Harlem. This ain’t SoHa. This is Harlem.’ It’s definitely something that’s going on nationwide and we can’t ignore that locals [must] be a part of that community and feel included in all the job creation and all the development that’s going on.”

The pain of Detroit’s 1967 rebellion still lingers. But it’s important to learn from mistakes so that the past is not repeated. Analysts believe Detroit is on the verge of a tech boom. It’s a major opportunity for the city of Detroit to fight back and right its wrongs.

“I think the biggest thing that we can do to make sure urban Detroit is included in this tech resurgence that’s happening is to include its local residents,” Alonso said. “Start at the local elementary schools and the high school levels. Tech can give back. They can benefit from creating and developing the students so that they learn how to code. So that they know math, science, and engineering. Also, introducing tech as an option in high school as a career option. Giving them internships and allowing them to come in and see how it is to be in a work environment in the tech industry. Giving them jobs. Even some unpaid internships. I remember when I was coming up, I did a lot of unpaid internships. But what it did was it taught me to think bigger than the environment that I was surrounded by. So those are things that I believe that the tech industry can do to help the city. And the city will help the industry as well with a whole new diverse workforce and that can only better the situation.”

[cigallery]