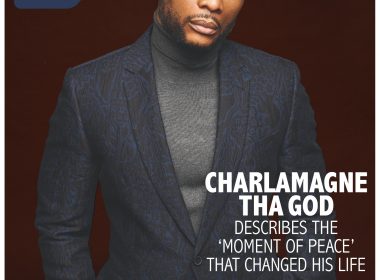

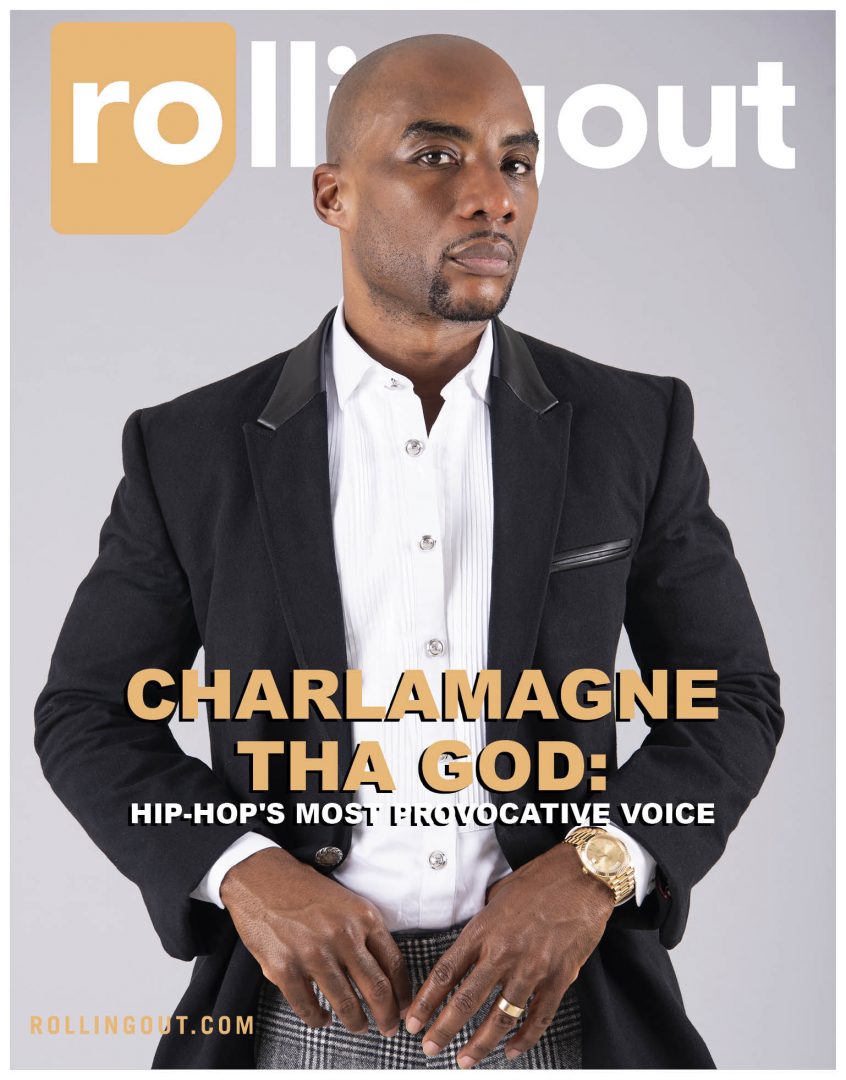

Lenard Larry McKelvey, professionally known as Charlamagne Tha God, may be the most “woke” Negro in America. His unapologetic celebrity interviews catapulted him to pop culture fame after a long and particularly creative career track in New York City radio.

East Coast listeners were all too familiar with the “shock jock” mentality that is synonymous with New York veejays, but the chances of finding substance underneath that shock are usually slim to none. “I always say I’m ratchet and righteous,” he laughs. “It’s about towing the line, finding that balance.”

Charlamagne’s quest for balance has made the hit morning show, “The Breakfast Club,” a place where listeners can be equally educated and entertained. He is also co-host of “The Brilliant Idiots” podcast with comedian Andrew Schulz. Charlamagne became a best-selling author in 2017 with his first book, Black Privilege. The autobiographical account of his “‘hood-to-all-good” lifestyle connected with fans and put him in that category of young, gifted, educated and Black.

His ability to instigate trending topics and influence cultural progression has made Charlamagne a perfect example of a new-age Renaissance man. Over the last five years, Charlamagne has transitioned from the co-host with no couth to possibly the most relevant voice in pop culture. His bullying antics have slowed down, and his innate journalistic instinct has become more apparent. His empathetic one-on-one interview with a very troubled Kanye West received more than two million views, and his interviews with music industry executive Lyor Cohen and rapper 21 Savage immediately went viral.

Do you believe technology is taking us further away from being truth tellers and instead allowing everyone to have their own brand of news or truth?

Of course. It also allows us to pick and choose what we consider news. We had Andrew Gillum on “The Breakfast Club” back in February and again in June, so when you see headlines saying media wasn’t covering him, that isn’t true. Those interviews get less attention than when Mo’Nique is barking at me, but we cover as much as we can.

Do you believe we are desensitized as a community because of what we are constantly inundated with?

We are totally desensitized, but it’s been that way. You see people murdered, stabbed, blood everywhere, and it’s all on your timeline. People are also easily manipulated by what they see. This can be a good thing, but it’s mostly used irresponsibly. I’ve used it to push certain social issues that are important because I know if I get certain people to post others will follow, so it brings attention to certain causes, which is cool.

What did you think about the most recent interview with Kanye where he apologized for his controversial remarks on slavery and the Trump “MAGA” gear he wore?

The man apologized, and I hear people saying that they don’t believe he was genuine. I thought that’s what an apology was. If someone says they are sorry about something, what else do we want him to do?

Did the recent attention to mental health issues inspire your new book, Shook One?

Yes and no. I was diagnosed 10 years ago with anxiety, but I realized I always dealt with it. Back when I was in the streets, I just thought it was part of the lifestyle. Honestly, you could see how someone living that lifestyle could suffer from anxiety because you aren’t doing the right things. There are always consequences. You got to constantly be watching your back. But for me, once I was out of that lifestyle and things are good, [the] family’s good and you still are feeling those same anxious feelings, then you know something is wrong.

You mentioned Mobb Deep’s record “Shook One” in your first book. Was it by accident that song became the title of the book?

The song at the time described where I was. I named it “Shook One” because, growing up, that was something you couldn’t be, especially as a Black man. You couldn’t be shook or nervous. It’s seen as weak, and you’ll get eaten up in the streets if someone detects that. But if you suffer from anxiety, it’s there. You learn to hide it. No one wants to be called crazy or think they are crazy.

Was there an incident that acted as a catalyst for you to go to therapy?

It’s just something I’ve always wanted to do for years. When you are the go-to guy for other people’s issues, you have to ask who does the go-to guy go to? [It’s] one of those things you ask people who [are] already going about, listen to how it has benefited them, and then make the decision to go for yourself. [In the] same way I can go to the gym three or four times a week, why wouldn’t I make the same investment to be mentally healthy?

How did you learn to manage your anxiety after your diagnosis?

I’ve always had my anxiety managed. I’ve always known how to deal with that irrational fear that pops up in my mind. I know how to change the station in my brain. My first attempts at therapy were me trying to get those thoughts to stop, period, but you learn that’s not realistic. I really thought something was wrong with me because my brain would go to the worst possible scenario immediately until you realize that’s what anxiety is. So my therapist has taught me more exercises to bring me back to center. But I’ve always pretty much been able to manage; just now I’m able to manage better.

Pre-orders for the book have broken Amazon records, and you still have almost a month before going to print. Do you think this is because of the subject matter or because of the success of Black Privilege?

Probably both. But, whatever the reason, it’s a blessing. In both cases, I’m just sharing my experience in hopes that it helps people.

You are doing a master class at rolling out‘s RIDE conference, and your session deals with the importance of entrepreneurship. In your opinion, why is entrepreneurship so important to the Black community?

Like Jay-Z says, financial freedom is our only way out. I don’t know why Black folks keep waiting on the White man to come help them. It’s obvious he isn’t coming. Entrepreneurship is the key. We have to teach our children to own their own businesses, and not only that but [also] to hire other Black people in those businesses. We have to hire each other and become patrons of each other.

Written by Christal Jordan

Photographs by Collis Torrington