Throughout history, there have been many battles that have been forgotten. One such battle that the British would like to forget is the Battle of Isandlwana, which took place on Jan. 22, 1879, as part of what was known as the Anglo-Zulu war.

The Zulu empire stretched over most of South Africa under the leadership of Shaka, regarded by many as a military genius. His empire stretched along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to the Pongola River in the north and most of Natal province. After Shaka’s assassination, the Zulu continued to grow. At the same time, the British Empire also began to exert its influence leading to a direct conflict with the Zulu. During this time in history, British troops occupied India and other nations and sparked the phrase “The sun shall never set upon the British Empire” because of its vast hegemony in the world.

During the mid-1870s, it was decided that Britain would continue its imperialist expansion by invading Zululand, but it needed a pretext. A series of demands were presented to the Zulu King Cetshwayo, including the dispersal of the Zulu army and submission of legal authority to the British crown. Despite his attempts at diplomacy, Cetshwayo realized that war was coming to the Zulu. The Zulu army was armed only with spears, cowhide shields and a few muskets and rifles, but it was more than 20,000 warriors strong. On Jan. 9, 1879, a force of 15,000 British troops armed with the latest rifles, cannons and rocket batteries crossed the Buffalo River into Zululand. Because of its racist disregard of the African military mind, the commander in charge split the British army into three columns of troops. The main corps force consisted of 7,800 British regulars. When word reached Cetshwayo of the British advance, he issued the following order: “March slowly, attack at dawn and eat up the red soldiers.”

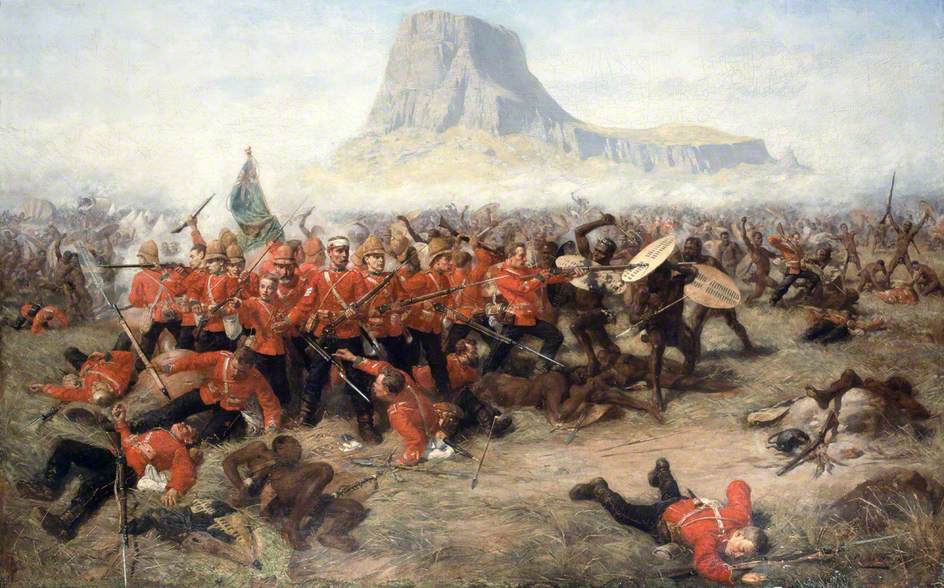

Soon, the Zulu army was on the move and its ranks swelled to close to 24,000 warriors who traveled at night, using the terrain and avoiding major engagements with the British. The British commander at the time was Lord Chelmsford, who gathered his forces at Isandlwana and failed to set up any defensive measures as he thought the Zulu were incapable of mounting a major attack. He further divided his force into ranging parties to engage what he thought were a few thousand Zulu warriors. That mistake was costly because as Chelmsford was relaxing, the Zulu quietly surrounded his camp. A group of British scouts chasing after a small number of Zulu into a valley saw more than 20,000 Zulu warriors sitting in silence less than 7 miles from the British camp. The scouts ran and were pursued by the Zulu forces back to the camp where the British reacted in shock.

As the cry of “stand to” echoed down the British ranks, the Zulu surrounded the British and attacked with a formation that Shaka had created decades ago called the “Horns of the Bull.” It consisted of a mass center of the oldest and most experienced warriors, with the younger warriors on the flanks. As the center body (bull) attacked the British, the flanking Zulu (horns) encircled the enemy. Over 1,500 British troops met their death at the end of a Zulu spear. The Zulus then fled back to the countryside to the dismay of the British. It was called the worst defeat of a modern army by primitives in British military history. Ultimately, the Zulu lost the war but the Battle of Isandlwana remains an example of victory despite overwhelming odds.