“There are years that ask questions and years that answer,” said author and cultural anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. When we look back at 2020, it will be hard to tell which that year was. The long-simmering cauldron of Black anger and resentment toward an America that has ignored grievances from Black Americans came to a head in 2020 to answer some of the questions that have been posed by Black people for more than 400 years.

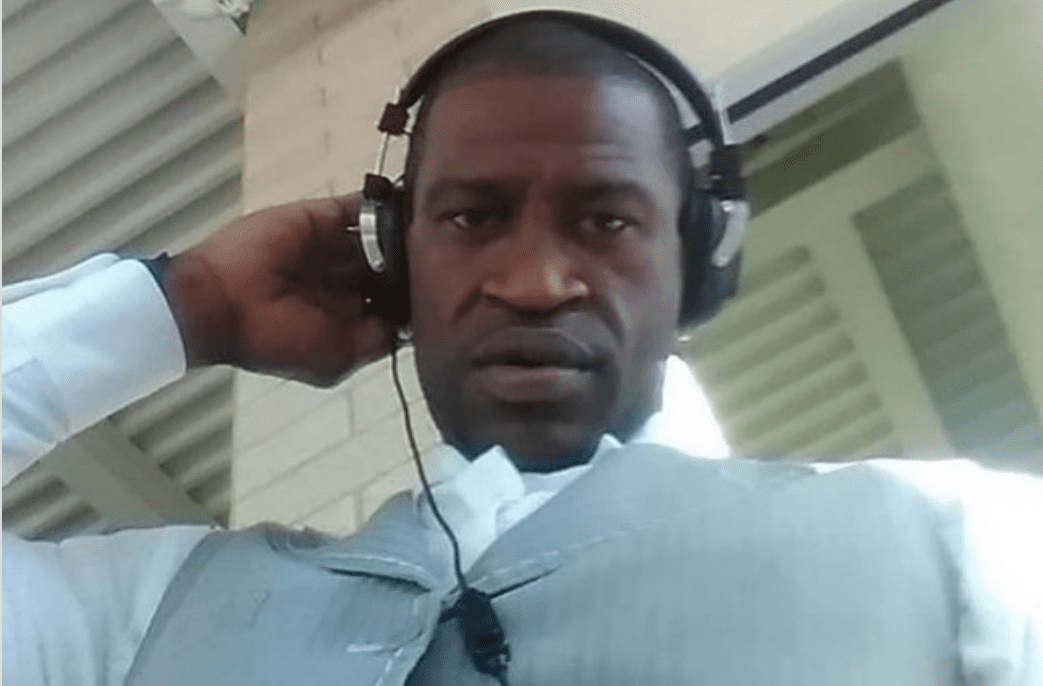

The world was forced to stop and really listen as protests stemming from the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis were broadcast across the world. When an officer pinned Floyd to the ground with his knee for more than eight minutes resulting in his death, it brought flooding back all the deaths, indignities and dismissals from those who said Black people should just “get over it.” Now the world was watching and, frankly, it couldn’t turn away. Protests spread first across this country and then around the world, and just like pulling a scab from an unhealed wound, every sector of our lives was found to be raw from the constant irritant of systemic racism. The confluence of events — COVID-19, a quarantined public, unemployment, a tanking economy, failures of the president — conflated as never before.

Black artists fight back

In the 2007 documentary Colored Frames, artists reflected on the place of Black fine art and artists in the Civil Rights Movement and riffed on their experiences, inspirations and influences. Self-described “people’s painter” Benny Andrews, to whom the film is dedicated, spoke of having to “go out and fight” for mainstream recognition of Black artists. The events of today could well be the response to their grievances. Andrews spoke in his capacity as co-chair of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, which protested a 1969 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art titled Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America.

Continued on the next page.