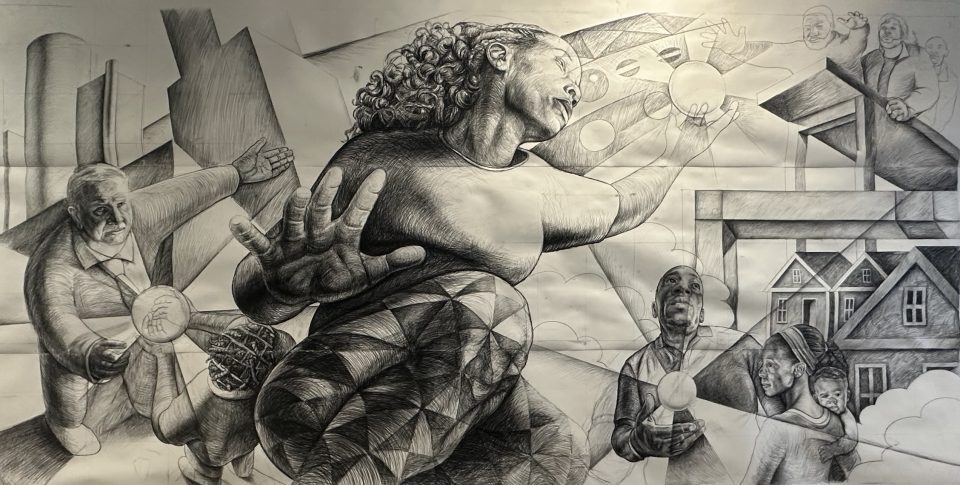

Visitors to the Huntington Tower in Detroit are greeted by a larger-than-life mural curated by Flint, Michigan native Hubert Massey. Massey’s process for determining what works to create come from years of studying various fields beyond art, including math, science and history.

Recently, Massey stopped by rolling out to discuss the spectacular mural in the Convention Center,

What is it like to be able to stand on a crane and begin with a vision in your mind and bring it to fruition on the walls of some of the countrys most impressive structures?

It’s almost a spiritual experience. When you do pieces like that, you know the artwork is bigger than yourself, and the purpose is bigger than yourself. Once you realize what your ability and capabilities are, the hard work you put into it to get to a certain level, then it comes to a point where [you ask], “So what’s the purpose? What’s your purpose?”

I know my purpose is bigger than what it is I produce, but it’s about impacting and celebrating African-American experiences.

Why did you draw inspiration from artists like Charles W. White and keep that torch alive?

Because I study a lot, not only a lot of Charles W. White, but I study the history of African-American experience through the arts. I’m just an extension of people who came before me. I’m an extension of John T. Biggers, Charles W. White, and a lot of the African masters. I’m a storyteller. I’m a person who tells our story about our culture, our history and stays true to the cause to make sure our stories are going to be told in a way that shows us in the best light possible. It has a lot to do with all that.

What is the story you’re telling children when they see the wall in Huntington Place?

I want them to dream that there’s a large possibility that you can do anything.

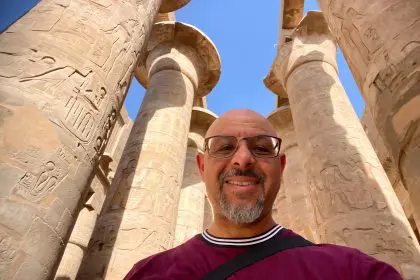

Part of my experience came from when I was when I was 21, and I had the opportunity to study at the University of London. Then, and I was an athlete, I played football, I ran track, I was a pro prospect in college. I, like some athletes, suffered a knee operation. When I suffered a knee operation, it just got me thinking.

When my professor came and said, “Look. We’ve got this program at the University of London in England, you should apply for this.” I did, and I ended up getting a scholarship to go there.

When I went there, my whole world changed. My whole world changed because now I was at the National Museum, the British Museum, I was seeing the Rosetta Stone, they didn’t know what the Rosetta Stone was, but then I saw some of the Egyptian mummies, and I realized how other cultures go into other cultures and adapt and remove cultures from other places like Africa, and then put them in museums.

Visiting Stonehenge was just a whirlwind of so much information. When I came back, I saw the world that I came from totally different. I said, “You know what? I’m going to take the same discipline I use in football and track, and put it into art.”

Doing frescoes, I told somebody, “I used to play football, and you played on a team, right? You had the quarterback and the guard, so I was a nose guard. I played on defense, but the fact of the matter is, it took a team effort in order to get from one side of the field to the other side of the field.”

I’m from Flint, but coming here to the city of Detroit, which is an industrial town, [I understand] the fact that it takes a team to create monumental pieces of artwork. It is not just me, but it takes the body of folks who contribute to the whole to make a great piece of artwork.

Michelangelo, when he painted the Sistine Chapel, it wasn’t him carrying 80 pounds of bags 80 feet up in the air. It wasn’t him plastering, he came to paint, but he had to have all these components in place. So I realized I needed to have an architect, structural engineer and fabricator. I started thinking even more outside the box. I started thinking more logistically on how to do great pieces of monumental artwork. I mean, look at the pyramids. It wasn’t one person that built them, it was many people that built that.

In what ways do you use anatomy in your art?

It’s the foreshortening. It’s to be able to see things in a different way. The whole thing is not being able to put the viewer in the average setting where we all see things that I love. I need you as a viewer, to not only come into my world but to stay in my world and to visit.

So I use this thing called dynamic symmetry.

Jay Hambidge was a mathematician, who broke up space using diagonal lines and stuff. This is all math. I always tell people if you were creating a mural that’s 900 feet long, 40 feet high, where would you start? It’s just like, you have a skeleton right? You have a skeleton, where would you put your heart? Where would you put your lungs? Where would you put your brain if you didn’t have a skeleton? How would you organize your organs so that you can function as a human being? Right? So you have structure, your skeleton has a structure. The line, the diagonal lines, the composition I create, I build a structure in order to create my compositions. That way, it gives me the ability to create to infinity, where you might be looking at a flat surface, but when you visually look, you’re looking at the depth of field, you’re looking at space that surrounds it, you’re looking at something that seems in proportion could be our portion, but yet it makes sense. It all works together as one. There’s science behind it. There’s math behind it, this encompasses so many different elements. Like I said, I got so into it, because I was very disciplined in football, and then I transferred that discipline into the art, the art of understanding how to grind pigments, how to make more colors and every day, how to give flotation to pigments so molecules can pass by one another. A red molecule passed by a blue molecule visually gives you a purple, and this is totally amazing.

To go back and work on a medium that is 102 years old, 1000s of years old, frescoes is the oldest form of painting on the planet. You had Diego Rivera in 1930s, come here and do the frescoes. He introduced frescoes to the United States. Of course, there were former frescoes and different advisors and environments. The Mayans were doing it, and the Aztecs, and the Egyptians, were doing all this around the same time, because that was the organic way of painting, the oldest form of painting is being able to walk into a cave, and the cave is all limestone. You take the red dirt, which is rust, and you paint the animals on the wall.

That’s a form of fresco.

So somebody came up with the idea of taking the limestone, scraping it off the side of the wall, turning it into a powder form, letting it air dry, and adding water to it to turn it into a paste, plaster on the wall. Now you have a form of fresco, taking the same rust, the same red dirt that you see on the ground, adding water to it, and painting it on the surface.

We have a chemical reaction that allows the pigments to stick to the surface. They say 100 years from the day you paint, a frescoes’ 100 years richer. A thousand years from the day you paint a fresco, it’s 1000 years richer. The colors, keep deepening and darkening over the period of time. What you’re seeing today is not what you’re going to be seeing 80 years from now, because it’d be richer and darker.

When I saw the painting, of what appeared to be a god, then I went inside the factory, and then I came back out to see who was visiting another planet and I could tell there was a whole universe. And you have to have all of this come out of your head?

Yep, and you know what? Naturally, most people are going to see things at eye level. We don’t look up; we look at what’s in front of us. That’s what we’re used to seeing all the time. But what if you were an ant, and you were looking up at a person walking over you or stepping over you? Look at the symmetry that you would get out of them. Look at the power that you would get out of that, or that person is reaching down to you, and you’re seeing the foreshortening. First, you see the hand, then you look past the hand, and you see the person’s face and the person’s body.

See, that’s what we normally don’t see.

So the whole thing is to be able to take the viewer and put the viewer in the situation where they see something that they normally don’t see all the time. Charles W. White did that. John T. Biggers did that. David Alfaro Siqueiros did that, and a lot of the Mexican mural painters did that. They tell their stories through the power of visual direction and the visual aspect of their environments.

What are you suggesting to people who are looking at this piece at Huntington Tower?

I’m suggesting that. I know, because we have a bank and money is probably the thing that people exchange amongst themselves. But what I’m trying to say is that the idea is what we all have. We all have value in our ideas. And if you don’t have an idea, you can’t make money, right? So you have to have an idea, and the idea is in the form of an orb that’s being passed from one person to another. The idea of raising a family, the idea of raising a community, that idea of a building. Building businesses, the idea of having the community come together as one idea.

Martin Luther King had an idea. Even when money is no longer being passed, the idea is still there. And it continues from generation to generation. So that’s basically what the mural is saying. The mural is saying we all have values and the values in our ideas on how we see ourselves as a person, as human beings, as people who are humanitarians.

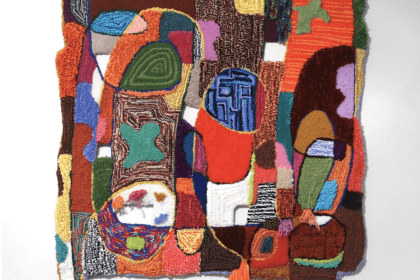

Why did you choose so many hues?

We are people of color.

Even the baby looks bluish green, but it works, though. It works. And it makes sense. We all have those colors in us. I’m just showing the diversity that we have, and the many shades and many hues we have in our culture, and how rich our culture is. If the color seems like it’s just really rich and vibrant, it’s because that’s who we are as a people.

I felt like it was moving. It felt as though the colors were moving because my eyes were; it was so warm and cool. It felt like it was a tapestry, and I could feel on what they were wearing. It came alive in that piece.

In fact, part of our culture is in the lady’s pants where she has the windmills.

There were windmills and quilts during slavery time when people were trying to keep track of their loved ones, from one plantation to another. So they sent quilts, and they sent coded messages a lot of times, but that’s part of our culture. Part of our culture is there because she’s an African American, the African American experience, but yet she’s still passing ideas to the next generation so that we can keep on elevating ourselves.