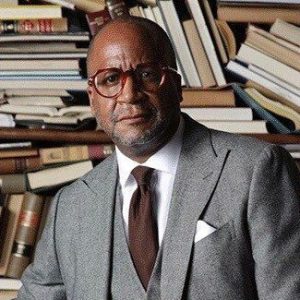

Dr. Andre L. Johnson, a native Detroiter, is the founder, president and CEO of the Detroit Recovery Project Incorporated, a nonprofit Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic that delivers services to more than 3,000 people annually.

Known internationally for his work in the field of addiction, Johnson was recognized by former president Barack Obama as the 2016 Champion of Change for Prevention, Treatment and Recovery. He also is a board member of the Wayne Center, an agency that provides services for the mentally ill and the developmentally disabled.

He took a few moments to talk with rolling out publisher Munson Steed about addiction and recovery.

Munson Steed: For people who don’t understand what recovery is, what is being in recovery?

Andre Johnson: Well, I’m glad you asked that question. Recovery is a way of life [sic] where we’re actually encouraging individuals to live a drug- and alcohol-free lifestyle. It’s remaining absent from drugs and alcohol. But it requires change — a change in one’s attitudes, behaviors and actions.

MS: For those who have never had the opportunity to enter a 12-step program, why is a 12-step program important to recovery?

AJ: Well, let me just step back a minute and just say, you know, addiction really is a way of life for some people that become extremely self-destructive — whether you are using drugs, whether you are addicted to gambling, whether you are addicted to sex, or whatever your addiction may be. In order to recover from that addiction, it’s gonna require some change, and it’s gonna require some support. So, when you ask the question about 12-step meetings like Alcoholics Anonymous [and] Narcotics Anonymous, these are support groups for individuals who have experience struggling with addiction. It’s a place where people can meet people who look like them and share some of the same experiences; it’s a place where people can be empowered and also find some hope because addiction can sometimes breed a lot of stigmatization. It breeds a lot of embarrassment, guilt, and shame, and people who are trying to overcome addiction need environments that are supportive and empowering.

MS: What should be their first efforts to really seek help?

Johnson: I think it depends on the individual resources. It also depends on what community people live in. Here in the Detroit area, where we’re operating, [we have the] Detroit Recovery Project centers, both on the east side and one on the west side of Detroit. There are some communities where treatment is not always accessible, but there are also opportunities for people to seek out professional help and to seek out 12-step support groups. So, if somebody is looking and watching our video today, I think it’s important that they can very easily Google where the nearest AA meeting [is at] or a meeting or treatment facility or therapist that specializes in addiction.

MS: What are the concerns that you have with the legalization of marijuana and how it will impact addiction in the black community?

Andre Johnson: Well, I think that addiction has always, you know, historically, been prevalent in the Black community, and addiction has devastated the Black community. When we look at our history — the heroin epidemic in the early 70s, the crack epidemic in the 80s and 90s and now we’re in 2024 — [sic] addiction has never rested in the Black community. What’s happening now is that more drugs are accessible — and marijuana is considered a drug, although some people use it for recreational and medical purposes.

But the more accessible drugs are in any community, people are gonna use them. And for us in the Black community, we’re seeing more and more young black kids subscribing to marijuana usage at an early age. Now, they are at a point where they justify using marijuana in terms of “Oh, I have anxiety. Oh, I have stress, and I need marijuana to help with my anxiety and stress,” not knowing that it does have a physical aspect to impacting their developmental process in terms of the cognitive skills that are impacted by marijuana usage. We do know. In our Black community, we have a significant number of high school dropouts. It definitely has an impact on people attending school, and it impacts attendance. It impacts the ability to really study and do the things you need to do during your early years of development.

MS: Many times a person needs something called a recovery coach. What is the value of having those individuals in your life?

AJ: Recovery coaches are paid positions that meet individuals in their respective communities and support them in their respective communities. A major part of the support usually is we look at four areas: emotional support, companionship support, instrumental support and informational support. Let me just give you the difference between the different areas of support. Emotional support is helping people to build what we call emotional intelligence, but also have an opportunity to interact with the individual that can provide that love, that genuine care, concern, empathy — you know, having somebody in your life. That brings empathy into the room, because [when it comes to] addiction some people don’t always have empathy for people who have suffered from addiction. Some people look at addiction and just have a very negative concept of addiction. And so for us, the recovery process is a process of empowering and providing hope and support and meeting the individual where they are. And I think we’re working, [sic] constantly to break down the stigmatization that comes with addiction.

MS: Can you describe the stigma?

AJ: You know, some people look at it as a moral deficiency; it’s not a moral deficiency. Addiction is an illness, and the illness has to be treated just like [physical illness]. If you’ve got high blood pressure, you’ve gotta get professional help. It also requires some lifestyle changes, and the beauty of the recovery coach is it’s always an individual who has already experienced a lifestyle change. Generally, they are people who have been in long-term recovery; they can share their journey, they can share their experiences, and it gives the individual an opportunity to identify with people.

Now, a 12-step sponsor and the recovery coach have a different role. The 12-step sponsor is an individual who has a working knowledge of the 12 steps, who does and embraces spiritual principles that can help individuals in their recovery, journey and process. And so again, I think, for us, it is really providing individuals with the support that they need. And that’s the beauty. Now, the sponsorship is generally an unpaid role that people take on. It’s a, you know, part of the 12-step philosophy has been that you can only keep what you have by giving it away. So it’s just this continuing opportunity to help reinforce the recovery process; the sponsor who’s supporting the person and walking and teaching them the 12 steps, they’re also reinforcing, reinforcing their own recovery, and they also are getting outside of themselves.

That’s good because … sometimes individuals become extremely self-centered. Breaking that self-centered cycle requires somebody who has experienced it. And that’s really the beauty of a recovery coach. The beauty of having a sponsor is having somebody who can really help with the process of recovery because the process of recovery is a journey — it’s a never-ending journey. You never really get well. We say recovery is a daily process, and that’s part of why we say just taking one day at a time. Sometimes taking it one day at a time can take the pressure off of people [in order to] able to live in the present, be able to live in the here and now, and be able to just embrace today. All the challenges that today have can be overwhelming for some people, so building that recovery foundation at an early stage is vital to individuals being able to enter what we call long-term recovery. Long-term recovery is something we refer to when an individual has been in abstinence for at least five years or more.

MS: Even after they find themselves in recovery, they may still have issues. What is the value of being able to go and get professional therapy and mental health support to also help your recovery?

AJ: Well, therapy again, it’s an opportunity for people to have a safe space. It’s an opportunity for people to perhaps make peace with their past. You used the word earlier: trauma. That is something that I think historically in some Black communities where people have grown up experiencing trauma [never had]: they never really found a safe space, never really had a safe place, never had the right opportunity to express some traumatic experiences. And so, even when you put the drugs and alcohol down, [it can still be a struggle] if you haven’t taken time to have an opportunity to [work with] somebody, particularly a professional that’s been trained in the trauma space or a person who’s been trained about trauma.

What we call trauma-informed care is our approach to really creating that safe space that ultimately can help people find healing and make peace. You know, when we talk about trauma, I remember years ago I talked to a young lady who I knew had been struggling with addiction for a very long time. She had been through our program at least five or six times, and the last time I had talked to her she was 10 years clean. I knew she had five kids. She was, at the time, about 40 years old, and most of her kids she had somewhat abandoned because of her addiction. I asked her, “After being clean 10 years, what’s your relationship like now with your kids?” And she said, “l have no relationship with my kid… My first four kids were by my cousins, who molested and raped me when I was a little kid.”

And she said, “You know, it’s hard to look at my kids because, every time I look at my kids, they remind me of the molestation and the rape.” She talked about how her family had disowned her and referred to her as a promiscuous young lady. So now, we’re talking about a woman who had this insurmountable amount of embarrassment, shame and guilt. Unfortunately, she was in a situation that she had no control over when she was young, and so now she’s an older adult, and still needs healing. She still needs to make peace within herself, just to be able to build a more healthy cohesive relationship with her children.

So, we see a lot of trauma with women in recovery, a lot of domestic violence, a lot of abuse, a lot of, you know, dysfunctional households that individuals grow up in — and those are some of the contributing aspects that exacerbate addiction. So, we have to look at addiction in terms of what people are trying to feel: what are they trying to hide, what are they trying to run from, or what are they trying to overcome? Once you put the drugs and alcohol down, there’s something we often talk about in the 12-step program: we gotta work on the inside. We gotta work on your character. We gotta also, in that process, be able to let go of our past. You know, sometimes you can’t really grow and move in the future because you’re constantly looking in a review mirror. We’re about paving a new way forward. And it’s a process; It’s a journey. And trauma is nothing to be taken lightly, I think. Sometimes, people take it lightly, but post-traumatic stress disorder is real.

I was talking to a young man yesterday who has spent 25 years incarcerated, and he said, “When I got out, I didn’t have no issues with drugs and alcohol. But I did have issues with being in large crowds. I did have issues with being in rooms with two or more people [sic] because I learned that I found myself experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder from being incarcerated a long time and constantly watching my back while I was incarcerated.”

And so, I think it’s really we [sic] as therapists, we try to understand and meet a person where they are but also help them to see that their environment often impacts their ability to in some cases develop anxiety [and] in some cases develop depression. And it’s really, you know, helping to improve one’s self-awareness. And I think once you have some self-awareness, and you’re motivated to take action and change — that’s when the healing in the recovery process starts. Recovery: it’s an inside and outside job.

MS: What about having to do an intervention on those family members who are drinking too much or on drugs? What’s the safest way to approach an intervention with that family member or loved one?

AJ: I think the safest way is to identify an interventionist who has experience with families. For me. I’ve been trained as a family interventionist, and my approach has been really embracing the family throughout the entire recovery process because a lot of times the families have not really done a lot of therapy or work. One of the processes that we take is a genogram. We look at, you know, the individual’s history in terms of grandma, great-grandma, great-great-grandma — and we usually see these patterns of alcohol. You know, alcoholism in some cases [is] on both sides of the family, the maternal side and the paternal side of the family. We see a lot of dysfunction: divorce, a lot of trauma. In some cases, we call it historical family trauma that’s never been resolved.

So, it’s really when we talk about family interventionists, it’s really looking at the entire family unit and pulling the family unit together to have what we call like a strength-based approach. [This is when] everybody has to participate in this recovery process for the family member that’s suffering, but also everybody looking at it and taking it and supporting each other as a family versus coming together as a family and placing blame or adding to insult shame or guilt. It’s more an approach that [sic] says, “Hey, let’s look at our history and let’s change the course of our history right now. And let’s set some family goals and [sic] how can we communicate with one another, [what is the] language we use toward one another. It can be having a family activity once a week, just taking baby steps to help. Ensure that the recovery person has a recovery family and, a conducive environment because recovering people, especially those coming from families that sometimes don’t always understand the nuances associated with addiction. [Some people in recovery come from] families [that] may come from an approach where you know you just need prayer; well, prayer hasn’t been working for that individual. You know that individual needs some action, that individual needs some support, and that the prayer didn’t work. Not that prayer does not work, but we gotta take another approach.

And I think that’s the beauty of having an interventionist that can say it [and] help establish ground rules. Because sometimes people can come together as a family and start talking about all the negative stuff, and it’ll just breed the negative energy in the person who’s been identified as the one who’s suffering. And now he or she can start experiencing emotional abuse. It’s really being able to identify the emotional abuse that often happens in families, the inability to really have a conversation — and it’s a courageous move. It takes courage for families to come together and work together. It takes patience; it takes time; it takes commitment; and it takes everybody working together as a unit. And I think the more families that can really embrace the concept, [the better] individuals do in their recovery process. Statistics have proven that individuals who have the family to support their recovery process, [their chances of long-term recovery] can be increased by at least 70 percent at the time.