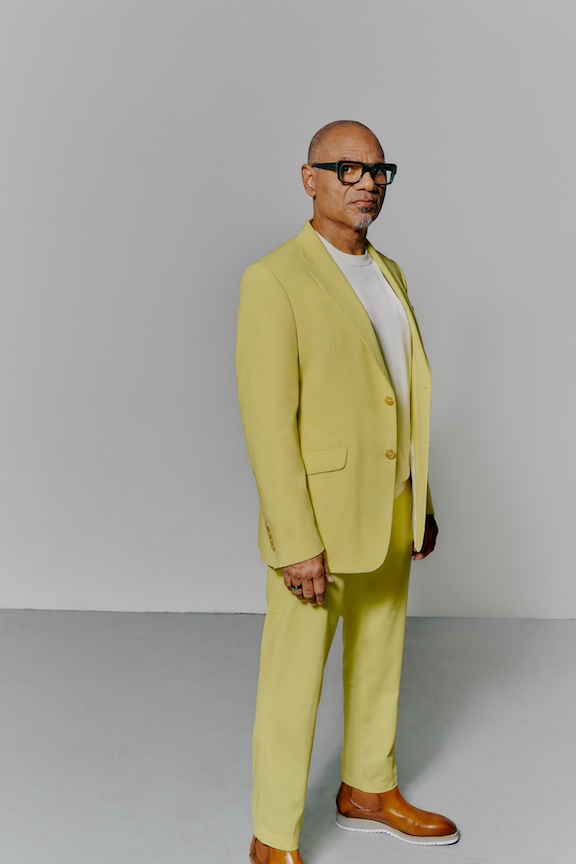

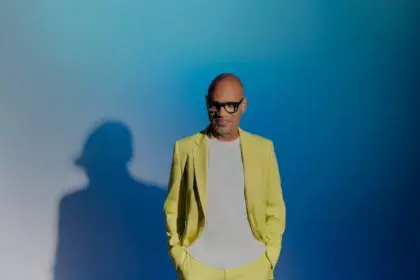

Grammy-nominated saxophonist Kirk Whalum has masterfully bridged the realms of spiritual and contemporary jazz throughout his illustrious career. In an intimate conversation with Munson Steed at Star Studio, Whalum delves deep into his latest album “Epic Cool,” while sharing profound insights about the spiritual essence of jazz, his HBCU experience, and the influential figures who shaped his musical journey. With 12 Grammy nominations and countless collaborations with music icons, Whalum’s artistic philosophy embraces both technical excellence and spiritual depth, creating a unique sonic experience that transcends conventional boundaries.

What should people be listening for when they are listening to your creativity and the journey that you’re taking them on?

Well, thank you for putting me loosely in a category with the great Pharoah Sanders, and allow me to say that Pharoah was the manifestation of something that happens when the divine, although not obligated, is pleased to join us in the creative progress process. In other words, not so much us representing God, but God taking part in what we do. So when people are impacted by our music spiritually, sometimes it goes without them kind of knowing what’s going on, ‘Why do I feel better, or what am I feeling?’

Can you share your first experience seeing Pharoah Sanders?

I want to just quickly say that the first time I heard Pharoah Sanders, I was about 22, and he was playing at a little jazz club in Houston. I was at an HBCU called Texas Southern, but I went to that club, and I was just riveted. I saw, and I still stick to the story at 66, I saw what I would consider to be the first and only miracle I ever saw happen, and that was that he was playing this thing, he was just going crazy going, and in that moment, I will swear to you today in 2025, he took his mouth off the mouthpiece, and the sound kept going, and then he put his mouth back on there. So, in other words, to say that what you in your introduction, talking about the spiritual core of this music, Pharoah Sanders literally did that, and I saw it.

How do you view the spiritual aspects of jazz?

The resonance of the bowl, because he was way into the Eastern mysticism, and it’s something that I’m into now. I’m a Christian, I’m actually Catholic, but the mystic part of it, in other words, the mystics who wrote so eloquently about the fact that the reason they call it faith, is because you can’t prove it, it’s not empirical, but you can prove it when you put your instrument in your mouth, you bring God on the scene. And I always say we can break and enter into people’s soul, especially as instrumental musicians without they don’t have any recourse. In other words, you don’t have an alarm system to keep me out, Pharoah could get in your soul, but the good thing is that he wasn’t in there to steal anything, he was in there to deposit something of beauty, of meaning, of worth.

What motivates you to create and compose bodies of work?

There’s the commercial element that all of us who like to have a place to record and a place to live, and a car to drive have to consider that. I remember the great Charles Lloyd, who also is from Memphis, where he was channeling something so big and huge, and he’s still doing it, but it came out in such a way, where it was forest flower and millions of people in Russia and in Japan and all over the world wanted to hear him play that song. So there is the commercial element, and it’s undeniable, and I am not ashamed of that, I have a family, I have grandkids.

When it comes to composing, I’m thinking about the masters, Mary Lou Williams, speaking of Catholics, Bob James was my compositional mentor, if it was simplistic, it was simplistic and profound at the same time, Westchester lady, he’s gonna be composing something that has its roots in all this amazing black music in particular, and just the great American and international composer. If I play, if I write a song that I know is probably going to get played on Smooth Jazz radio, it’s still gonna have something in there where you go, I see what you’re doing.

What inspiration did Joe Sample give you?

Joe Sample was from 4th Ward because he was way out East, and not Forestbrook or Cashmere, one of those schools way out there, and that Texas big old, huge, connected international city ethos, is what impacted me so deeply when I first went to Texas Southern, where Joe had gone and left Ian Wilton and all the Crusaders and the Laws family and all of them were gone by the time I got there in 76, but their legacy and dignity, and just the profound impact of their music, was still lingering. And as a composer, Joe Sample is singular, I don’t think there’s anybody like him.

What’s it like when you’re playing with other creatives and there’s a merger happening?

I’ve been in the studio with Joe and Lalah, and we’re recording a song called “When your life was Low,” and so I’m sitting there, by the time we get to the middle of the song, I’m in tears. It’s not like a gospel song per se, but it’s so deep, it’s connected to that same well of emotion and spiritual beauty.

First time in rehearsal, we finished the song, and I was like Joe, I pushed the talk back button. I said, “Joe, no way in the world. We going to finish this and not go back and reprieve it like the gospel people, like the song is over. Oh, no, it’s not over yet.” That’s the one time I can say in my whole career, I gave Joe Sample advice, and he took it.

What three emotional words would you want people to take away from your legacy?

Grace, gratitude and healing, those are the things that I want to be an ambassador of, grace, gratitude, and healing. I want people to sense that when they hear me play, or they hear one of my songs.

The context is so amazing, contextualized with so many unbelievable musicians, and, by the way, the NAACP awards, Samara Joy is in the same category as me, so I’m happy to just be standing up as she receives that award, but I performed with her a few times as well, but I mean it’s just grace, gratitude, and healing. I hear that in her, I hear that in so many artists, I’ll say Jazzmeia Horn, Sheléa, Jonathan Butler.

And it reminds me, too, that as a jazz musician, sometimes we get hung up, because, as when we made this call I was already practicing on something technical, and when we hang up I will go back to working on that, but sometimes we forget that, that’s not the thing that really, that’s for us to prepare our vessel, as it were, to be used for God’s purposes. So there’s no shortcut to that, but that’s not really the thing that gets people, people want to feel you, and so but you have to be a vessel that you didn’t just show up with some mediocrity.

What was your experience at an HBCU like?

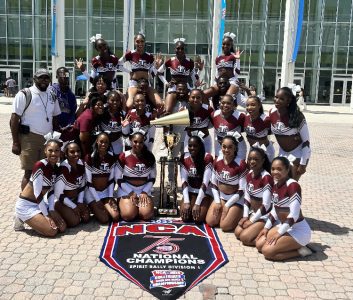

It was hard work, Texas Southern, the Ocean of Soul marching Band. I remember being here in Memphis at Melrose High, and they were like, “Yeah, guess what? You got a scholarship to go to Texas Southern.” I’m like, jazz! I get a jazz scholarship. What I didn’t realize was that the money to fund those programs comes from something called the marching band, because it’s all about people coming out to see the football game, but in that case, they really came to see the band.

I did not go to Texas Southern to march in the band. But guess what I did. I marched in the band and I hated it, but at the same time, when we hit the field, you felt it. You’re like, “Oh, wait a minute.” There’s a certain pride going against FAMU or against Southern, and you got to bring it. But it’s not just you. It’s us.

And that part of it was a revelation to me like, “Hey, it ain’t just about you. It’s about us, and here is your glorious opportunity to experience how powerful that is to be a community bringing forth not only a great, powerful sound, but bringing forth the legacy and dignity of our people.” That’s when HBCU was for me. It just gave me that beautiful connection, with my people. And then, of course, Texas, that was a whole nother thing like there was this whole big, huge thing, spiritual thing of Texas.

What’s your North Star now and how do you maintain it?

I spoke to you of my faith, that’s the primary thing, but if we talk about pedagogy, we talk about implementation of this thing. Jazz saxophone, it is important to have an avatar. And for me, that’s Charles Lloyd, not just because he’s from Memphis, my hometown, but he’s such a beautiful man, and he’s spiritually like just so full that it just leaks out, but the other part of it, his man keeping your ear to the ground with these bad, bad young players, I mean.

The female Saxophonists who are now making the Camille Thurmans, Tia Fuller, because this thing was very patriarchal for the longest time. Thank God for Mary Lou Williams, who was in there with a machete, chopping down and making a way for these young ladies who have come in and inspired me so much. The technique of it, is amazing, but also the women in my life musically who are not afraid of that spiritual core, whereas men are like. Oh, there’s a lot of men like that. Thank God for Pharoah Sanders, and others who were like, “Hey, if you think this is terrestrial, you’re wrong.”

How would you define ‘cool’ in this record and in jazz musicians?

I think it’s a paradox, on the one hand, you know that the atmosphere is filled with people who play better than you, that’s the humility part of it. Like you look around on this corner, that corner, you can look in your age group, a third of your age, and they are all killing it. I think the cool part is you being able to relax into it? That’s the thing that the coolest of the cool. Miles Davis just was so relaxed into that thing he was doing.

He had such confidence, it’s like people said it was arrogance, but it wasn’t that. It was just man. I know what I have. I know what I don’t have. I’m not trying to bring that, I’m bringing what I have, this is who I am, and you can do that with confidence, and that’s what cool is.

Is that what people can hear on Epic Cool – your confidence?

I think so, for instance, the title track, I’m playing the big baritone. It’s the first song I’ve recorded on baritone, but I’m so far back on the beat. I’m laid way back, kind of the West Coast part of all of this stuff, Jerry Mulligan, and Miles, too, but like you’re just so far back on the beat, you’re not in a hurry. So that’s I think that’s the manifestation of that.

Why use the word epic, and what emotions do you connect with in that particular record?

The title Epic Cool came from a buddy of mine, who’s also in the same age, middle sixties, who is a sports announcer in San Antonio, Don Harris. I sent a song to him before the record came out, and he said, ‘Man, that’s epic cool’, and that ended up being the name of the song and the name of the record.

In my head, it’s about people our age being faithful to stay in there and being faithful one, and being courageous at the same time to say, “Yes, I’m on the older side of this, but I have something important to say.” There’s a wisdom that comes with all those years and as well. There’s a gravitas, if anything, maybe epic equals gravitas, like there’s something that we have, that the bad, bad, bad young players they don’t have yet. They’ll have it when they’re our age. So I think, for the listeners, too, who like you’re in your sixties or seventies, you’re like, Hey? I want to connect with you. We got some energy to bring to you and connect with your energy like man, we still out here.

What’s your invitation to someone who hasn’t listened to your music?

This is Kirk Whalum, come check me out, as I do my best to get out of the way and present something that you will feel long after I’m gone. I think it’s that I mean, in fact, there’s a song on my new record. The record is called Epic Cool, but there’s a song called Pillow Talk, and, as usual, it’s a double entendre. It’s like the intimacy of that setting, and that song is so powerful. It’s like me playing way down low on the instrument, as opposed to, and it’s just very intimate and very tender.

So that’s the thing I would love to invite people to, is through a song like that, I know there’s so many impressive people who do what I do. There’s Eric Darius, Marcus Anderson, all these young brothers, but what I’m hoping I can do through a song like Pillow Talk is, I just whisper, you’re so close to me and it doesn’t have to be sexual, but that you feel the spirit, you feel something greater, something beautiful.