The story of MRSA begins just four years after methicillin entered medical practice in 1959. The bacteria had already developed resistance to the new antibiotic, demonstrating the remarkable adaptability that would make Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus one of medicine’s most persistent adversaries. Today, this pathogen affects hundreds of thousands of Americans annually and represents a critical public health challenge at the intersection of infectious disease and antimicrobial stewardship.

MRSA represents the leading edge of antibiotic resistance

The first essential fact involves MRSA’s place in the broader antimicrobial resistance crisis. While many bacteria develop resistance to specific antibiotics, MRSA has acquired mechanisms that render entire classes of antibiotics ineffective, significantly complicating treatment options.

The bacteria achieve this resistance through possession of the mecA gene, which produces an altered penicillin-binding protein that prevents beta-lactam antibiotics from disrupting cell wall synthesis. This single genetic element confers resistance to nearly all commonly used beta-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins, cephalosporins and carbapenems.

MRSA serves as a harbinger for the post-antibiotic era that public health officials have warned about for decades. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classifies MRSA as a serious threat in its Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report, highlighting the pathogen’s significant health and economic impacts.

Two distinct epidemiological patterns create different risks

The second key fact involves MRSA’s two primary epidemiological patterns. Healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) traditionally affects individuals with healthcare exposures including recent hospitalization, surgery, dialysis, or residence in long-term care facilities. These strains typically cause bloodstream infections, pneumonia and surgical site infections.

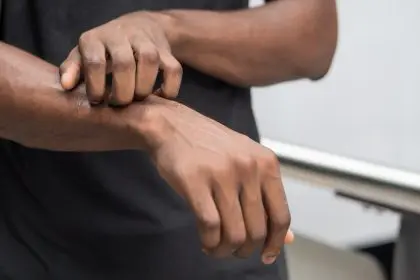

Community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) emerged in the 1990s, affecting individuals without traditional healthcare risk factors. These strains commonly cause skin and soft tissue infections, often beginning as painful “spider bite-like” lesions that rapidly develop into abscesses requiring drainage. CA-MRSA can affect anyone but disproportionately impacts athletes, military personnel, incarcerated individuals and others in close-contact living situations.

Genetic and phenotypic differences between these two MRSA types influence their behavior, with CA-MRSA strains typically carrying genes for Panton-Valentine leukocidin, a toxin that destroys white blood cells and contributes to more aggressive skin infections. However, the distinction between hospital and community strains has blurred in recent years as strains move between settings.

MRSA colonization precedes most infections

The third essential fact involves the relationship between colonization and infection. Approximately 2 percent of the general population carries MRSA asymptomatically, primarily in the nasal passages but also in the throat, axillae, and groin. This colonization serves as a reservoir for potential infection when the bacteria gain access to tissues through breaks in the skin or during medical procedures.

Among healthcare workers, colonization rates typically range between 5-10 percent, creating potential transmission vectors between patients. In long-term care facilities, colonization can reach 25-50 percent of residents, explaining the high incidence of infections in these settings.

Most individuals who develop MRSA infections are first colonized with the same strain, often for weeks or months before clinical infection develops. This understanding has led to decolonization strategies for high-risk individuals, including nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body washes, which have shown effectiveness in reducing subsequent infection rates in certain populations.

Transmission occurs primarily through direct contact

The fourth fact concerns transmission pathways. Unlike respiratory pathogens that spread through airborne routes, MRSA transmits primarily through direct person-to-person contact or contact with contaminated objects and surfaces. The bacteria can survive on dry surfaces for days to weeks, enabling environmental transmission particularly in healthcare settings.

Healthcare transmission often occurs via the transiently contaminated hands of healthcare workers moving between patients. Community transmission typically involves direct skin-to-skin contact during activities like sports, particularly those involving skin abrasions, shared equipment or common-use facilities like locker rooms.

Household transmission represents another significant pathway, with studies demonstrating that when one household member develops an MRSA infection, colonization often spreads to multiple family members. This household reservoir can lead to recurrent infections unless addressed through coordinated decolonization efforts involving all household members.

Treatment options remain despite resistance

The fifth essential fact involves treatment approaches. Despite its resistance profile, several antibiotics retain activity against MRSA, though options have narrowed as resistance to additional agents has emerged. Vancomycin has historically been the cornerstone of MRSA treatment for serious infections, despite its limitations including poor tissue penetration and potential toxicity.

Newer agents including linezolid, daptomycin, ceftaroline and telavancin offer alternative treatment pathways, though concerns about cost, side effects and the development of resistance to these agents limit their use as first-line options. For uncomplicated skin infections, older antibiotics including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline and clindamycin often remain effective.

Drainage represents a crucial intervention for MRSA abscesses, with studies demonstrating that incision and drainage alone may suffice for uncomplicated skin infections without antibiotic therapy. This approach helps reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure that drives further resistance.

Prevention strategies span healthcare and community settings

The sixth fact involves prevention approaches. In healthcare settings, MRSA prevention bundles have demonstrated significant success in reducing infection rates. These comprehensive approaches include active surveillance cultures, contact precautions for infected or colonized patients, hand hygiene emphasis, environmental cleaning protocols and antimicrobial stewardship programs.

These coordinated interventions have contributed to a 17 percent decrease in hospital-onset MRSA bacteremia between 2005-2011 according to CDC surveillance data. Some European countries including the Netherlands and Scandinavian nations have achieved even more dramatic reductions through aggressive “search and destroy” policies that identify and decolonize MRSA carriers.

In community settings, prevention focuses on wound care, hand hygiene, avoiding shared personal items like razors and towels, and covering wounds until healed. Athletic programs have implemented protocols including regular equipment cleaning, prohibiting shared items, and emphasizing prompt attention to skin abrasions.

The economic burden extends beyond direct medical costs

The seventh essential fact involves MRSA’s economic impact. The direct medical costs associated with MRSA infections in the United States exceed $4.5 billion annually, with hospitalization for MRSA bacteremia averaging $23,000 per case, significantly higher than methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infections.

These figures underestimate the true economic burden by excluding indirect costs including lost productivity, disability and premature mortality. One analysis estimated that resistant infections add $20 billion in excess direct healthcare costs annually and up to $35 billion in lost productivity in the United States.

The societal costs extend to antimicrobial development, as the need for new agents effective against resistant pathogens drives research and development expenditures that ultimately increase pharmaceutical costs throughout the healthcare system.

Looking forward, efforts to address MRSA encompass innovation across multiple domains. Novel approaches to prevention include vaccines targeting S. aureus virulence factors, though these remain in developmental stages after several high-profile clinical trial failures. Bacteriophage therapy, which uses viruses that selectively target bacteria, shows promise for treating resistant infections but requires additional research before mainstream implementation.

Diagnostic innovations focus on rapid molecular tests that identify MRSA and its resistance mechanisms within hours rather than the days required for traditional culture methods. These advances enable earlier targeted therapy and more effective infection control interventions.

Perhaps most importantly, MRSA has become a focal point for antimicrobial stewardship efforts that aim to preserve antibiotic effectiveness through judicious use. These programs represent a crucial response not just to MRSA but to the broader challenge of antimicrobial resistance that threatens to undermine modern medicine’s foundation.