One thing you never do is tell a woman that she’s fat or ask her when she’s due (inferring that’s she pregnant). Those insults will surely prompt a quick side-eye glance and in the case of most black women, a tongue lashing. To have the audacity to speak in a New York Times op-ed on our behalf and declare “black women are fat because we want to be,” is short-sighted and hazardous to your reputation. Considering blacks over-index in incidences of high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke and high cholesterol – which are all linked to poor diet, lack of exercise, income, education and socioeconomic status – is a strong indication that we don’t necessarily enjoy carrying the burden of obesity, this “extra weight.”

Why? It’s because it leads to disproportionately higher levels of death and disability in comparison to other races. I haven’t met many women who find premature death and chronic illnesses appealing.

In reading Alice Randall’s featured titled “Black Women and Fat,” it made me raise an eyebrow to say the least. Not sure what her end game was, or the reaction she was seeking. I can tick off a list. Outrage? Check. Self-promotion? Check (I did a Google search to learn more about the author and her completely unnecessary offering). A Counter? Check. Twitter’s 140 characters limit couldn’t handle my ire.

I applaud Randall for referencing the late Lucille Clifton’s 1987 poem “Homage to My Hips,” which opens with a self-observation, “These hips are big hips.” It was a teaching moment for those who are unfamiliar with this widely-respected poet laureate who honored her race and our strength in times of adversity.

Here’s where Randall fell short. A platform like the New York Times shouldn’t be taken lightly. To omit critical facts that the health gap is a result of cultural differences, lack of access to care and knowledge about proper exercise and nutrition, and in some cases genetic, is remiss.

Sure, my significant other, like your “lawyer husband,” has commented about my on-again-off-again obsession with the gym. His concern is not so much that I will lose too much weight and my curves will disappear. He wants to make sure I am not aiming to be a “Barbie” or too buff.

There’s a misconception that can be drawn from reading your feature that keeps women from being healthy and fit. There are black men who love voluptuous women, I have to agree. But she has to be alive for him to cuddle her, so her health is more important. You can have the figure and be fit. You don’t have to sacrifice your curves to be in shape.

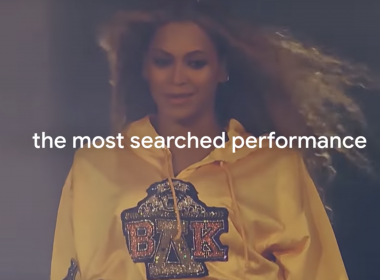

If “those many black women,” who you reference, held up a picture of Beyoncé Knowles-Carter or Viola Davis (curvy but fit) for those “sane, handsome, successful husbands [who] worry when their women start losing weight” if they prefer what they see in the photo or the 200 pounds jiggling in front of them, the answer would likely surprise them and send the zaftig women running to the gym.

Let’s be careful and cognitive when opportunities arise to have our voices heard that we don’t use the opportunity for self-aggrandizement or spark culture wars with neighboring cities, i.e., the Nashville versus Memphis rivalry reference was superfluous. You wrote:

“In black Nashville, we like to think of ourselves as the squeaky-clean brown town best known for our colleges and churches. In contrast, black Memphis is known for its music and bars and churches. We often tease the city up the road by saying that in Nashville we have a church on every corner and in Memphis they have a church and a liquor store on every corner. Only now the saying goes, there’s a church, a liquor store and a dialysis center on every corner in black Memphis.”

If this was an attempt to encourage black women to exercise, it was an epic fail. It was more an opportunity to bash, as if we don’t throw enough punches at each other with our reality television tastes and guilty pleasures.

I digress. —yvette caslin