The first indication that Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave might be the signature movie of the year if not a defining film of the new millennium, was the strong buzz coming from the even most grizzled and cynical movie critics.

“A masterpiece.” … “Brilliant.” … “Oscar-worthy.”

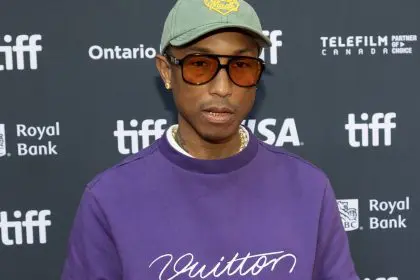

These accolades began coming in at a steady drizzle after 12 Years a Slave made its debut at the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado in August. But then the praise for McQueen’s soul-searching epic quickly intensified into a torrential downpour once the film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September:

“Easily the greatest feature film ever made about American slavery,” wrote The New Yorker.

“Raw, eloquent, horrifying and essential,” claimed Time magazine.

“12 Years a slave is a mesmerizing triumph of art and polemics,” says IndieWIRE

“Smashingly effective as a melodrama,” testified the New York magazine, while another publication added the film is full of “astonishing performances that’s practically a one-stop Oscar nomination shopping spree.”

When the credits rolled after journalists from around the country viewed the film at The Conrad in Lower Manhattan, they gave the blank movie screen a standing ovation. I had not seen that since Jennifer Hudson’s (eventual) Oscar-winning performance in Dreamgirls.

Get used to hearing McQueen’s name. Before he even began to make his first studio film (and third overall) with 12 Years a Slave, he had accrued such cachet and respect as a visionary, screenwriter and filmmaker that the first 20 minutes of his film Hunger was shown at New York University as an example of great filmmaking. And revered actress Alfre Woodard actually lobbied to work with McQueen on Shame, which she thought was the best movie of the year when it came out. Woodard barely allowed her agent to finish the question about possibly working with the 12 Years a Slave director before her response shot-putted out of her mouth with resolute force.

“Yes,” the regal thespian Woodard recalled at the film’s press conference in Lower Manhattan.

“No,” the agent advised. “We have to send you the script first.”

“No,” Woodard shot back immediately and resolutely. “Just ‘yes’ right now. I want to be a part of this film.”

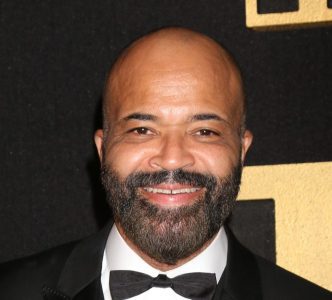

McQueen’s first two major motion pictures had garnered great industry buzz and critical acclaim. But now with 12 Years a Slave (opening in select cities beginning Oct. 18) he is about to be the center of Hollywood. He adapted the true story about freeman Solomon Northup (played by Chiwetel Ojoifor), a well-educated and respected musician living in Upstate New York (Minerva, four hours from New York City) who is a married father of two young children. One day Northup happened upon two unscrupulous promoters who promised to help Northup enhance his violin career with a tour of Washington, D.C. Instead, while in the nation’s Capitol, Northup is drugged and taken to a holding cell and soon shipped off to New Orleans. He was given a new name — Platt — sold for $1000 and goes through a series of slave owners before landing with the malevolent slave master Epps (played brilliantly by Michael Fassbender).

The movie, for which the balance of the film deals with those dozen years of Northup as powerless property undergoing harrowing physical and mental abuse, juxtaposes beauty and brutality with uncanny dexterity by McQueen, based on Northup’s 1853 book of the same name.

To crystallize this point, during one piercingly pivotal scene in the film, some people walked out during the Toronto screening, but the remaining thousands who watched to the end gave the film a prolonged and rousing ovation.

“Certainly some things some people aren’t going to be able to sit through and I understand,” McQueen said. “But the vast majority were there and gave us a standing ovation. And I just take heart, really.”

McQueen was destined to make a movie about black history and American history. But after he made his well-received debut feature Hunger, McQueen attempted to make a movie about Civil Rights activist Paul Robeson – a brilliant scholar, football player, orator and opera singer. McQueen was pegged to direct his second film (and second film to receive acclaim), Shame.

McQueen had discussed with his inner camp making a movie about a free black man during the time of slavery when his wife found Northup’s book, 12 Years a Slave, which most of the nation had no idea was even in existence.

Now that he had his hand on this undiscovered historical jewel of modern times, McQueen set out to make a movie that would blow down the narrow parameters of just race.

“I made a movie because I wanted to tell a story about slavery, a story which for me hadn’t been given a platform in cinema,” he said. “It’s one thing to read about slavery, to have these illustrations – but when you see it on celluloid and within a narrative, it does something different. And if that starts a conversation, wonderful, excellent, it’ll be about time. But I hope it goes beyond race. This film for me is about how Northrup survives a specific situation. Yes, race is involved, but it goes beyond that.”

It matters little that Steve McQueen was not born and raised in America and is now telling a story about the horrific institution of American slavery. His ancestors, much like those of many naturalized black Americans, were stolen from Africa and summarily dropped off in the New World. McQueen’s ancestors landed in the Caribbean — the British West Indies, to be exact — instead of going all the way onto United States soil. (McQueen’s family eventually moved to England where he was born).

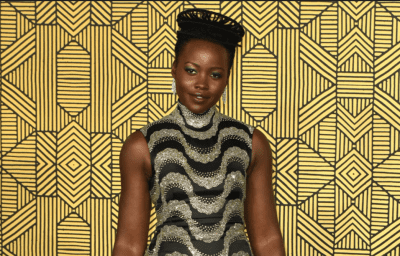

But he explains with eloquence and dead-on precision how he and the two non-American black actors in the film — Chiwetel Ojiofor who plays Solomon Northup and brilliant newcomer Lupita Nyong’o — are directly connected to the history of slavery in the Americas.

“The story’s not just an African-American story. It’s a universal story,” he said. “It’s a world story. My parents are from the West Indies. My father’s from Grenada which is where Malcolm X’s mother was born. My mother was born in Trinidad which is where Stokely Carmichael, the man who coined the phrase Black Power! was born. Sidney Poitier was born in the Bahamas. I’m part of that diaspora of people displaced by the slave trades. I’m part of that family. It’s our story. It’s a global story.”