A few months ago, I was peering out of my bedroom window as I chatted on the phone with writer Shelia Moses. I was being interviewed for her book Dark Girls (2014), a beautiful photo/essay collection of dark girls’ color-conscious stories based on Bill Duke’s 2013 OWN feature of the same name. A friend had identified me as a “dark girl” whose take on beauty would greatly benefit Moses’ work. What was to be a short “phoner” turned into hours of Moses and I chatting and laughing and even me crying about color codes in the Black community, infighting and barriers, then reclamation, identification and celebration. While I missed the photo shoot for Dark Girls and my interview was tabled, my time on the phone with Moses was perhaps the most cathartic dialogue I’ve experienced concerning my skin color in my adult life. I was on the phone telling Moses all of my sad “dark girl” stories — ones that are likely familiar to any other dark girl reading this article: being teased and told to step aside, my first crush (who was darker than me) laughing at me and asking if my lighter cousin was also interested, mean girls in high school comparing me to Doug E. Doug (based on my color and features), a college friend telling me I shouldn’t wear that red lipstick. … The list was long and painful and Moses endured it all. The lowest tale was one that’s nearly too painful for me to share here. It happened when I was a few years shy of my teens. I was riding in a car with older teenage boys (one was my boy cousin), and while I wasn’t exactly into boys just yet, I knew this was special. My lighter girl cousin who is just a few months older was in the seat beside me and we were grinning hard as the boys, all muscle and cuteness, told long jokes and cursed at will. I felt grown and free. At one point, we were driving past a group of dark-skinned girls. Where I’m from, New Cassel, Long Island, teens walk the main drag, Prospect Avenue, with no particular destination in mind. These girls were just looking to be seen and maybe spoken to.

The boy in the front seat directly in front of me was very light, he had green-grayish eyes and coarse but light brown hair. In our community, he was a prized unicorn. I knew that and a part of my young subconscious mind eagerly awaited his appraisal of the sauntering gaggle of cocoa-colored sisters who mostly looked like I would in about five years.

“Doo-doo girls!” he screamed and in my tender memory, his words rocked the entire car, rattling the very seat beneath me. “Doo-doo girls! Those are doo-doo girls. They’re the color of doo-doo!” His joke incomplete, he laughed and the other boy-men joined in, laughing at the girls walking by, who’d quickly been reduced from sauntering sisters to desperate wanderers in my subconscious. What he said next can’t be retold with sincere accuracy but the thesis focused on dark women being undesirable and just ugly. Though I can’t be sure, my mind believes he sat up, coiled around to stare into me like a serpent set to strike and spat those words, those ideas, into my young soul and spirit. The words tore into me. The meaning behind those words clipped some invisible wings that had already been weather-beaten by other instances. The message was clear: there is no love here for you, dark girl.

The kind of emotional trauma caused by those words is what I fight to avoid in my daily life as an adult dark girl. It’s why I only keep certain conscious people in my circle and whenever I see a little brown girl, I bend down and tell her how beautiful and smart she is. This world is too filled with trouble for dark people for me to allow even the possibility of more “doo-doo girl” stories into my journey. I abhor most hip-hop music videos, avoid the radio altogether and every semester, I spend weeks sharing with my black girl students the impact that lyrics in songs like “That Foreign” (Trey Songz: “Same old thing, yeah you know that s—‘s boring/American, you know I had to cop that foreign” ) and the now infamous “Right Above It” where Lil Wayne raps, “Dark-skinned woman, I bet that b—- look better red” must have on their subconscious. I tell them to avoid this heckling, to stay away from these insults, to nurture their thoughts of their Blackness like the coveted and enviable thing it is. Instead, they ought to seek more enriching experiences that will impact their concepts of beauty in positive ways: date brothers who love their hue, listen to music that uplifts: I even give a list that begins with “Brown Skinned Lady” by Black Star where Talib Kweli raps, “My brown lady, creates environments, for happy brown babies, I know it sounds crazy but your skin’s the inspiration for cocoa butter …”

In fact, last week I reminded my students to tune into “Light Girls,” which was being featured on the OWN network on Martin Luther King Day. While I knew there would be sad moments, in the end I was sure the information and discussion would inspire more dialogue and understanding. I, for one, was tuning in to hear traces of my lighter cousin Tamika’s story. While her light skin was certainly enviable when we were children, I watched as her teen years became a struggle due to her color. In junior high she was terrorized by the other girls — who were once her friends. They put crap in her locker, threatened her and told lies about her sleeping around. Today, Tamika actually remains basically friendless aside from very close family members and I know much of it is due to those scars when she was told she “thought she was all that” — which was so far from the truth. Therefore, I wanted to hear her story in Duke’s “Dark Girl” remix “Light Girls” and for the most part, I did. And I waited for the moment of epiphany and dénouement, for the “light” tales to come full circle and feed my students and me what I’d promised from the nurturing program on this nurturing network. But it never really came. In fact, at one point during the broadcast things became exceptionally tragic and traumatic.

During the “Light Girls” segment featuring brothers speaking about their dating habits, Black men ages 20-50 politicked in circles and personal interviews about their color “preferences.” The result was too frightening and deprecating to even believe. As Shelia Moses said on my Facebook page, it felt more like satire than open cathartic analysis, the latter being what one would expect on OWN. One brother said there are benefits to choosing dark women over light women, as dark women are willing to “serve” their man while light women might “think they’re too good.” Another explained that a dark girl is more willing to get her man soda at the movies. Someone shared he prefers dark women, but his tone was nearly patronizing, like he really wanted viewers to hear that he “actually” likes dark girls — which may make him special or deep or maybe crazy. Still, in the end, they all seemed to agree that the preference in society for all men is light skin. One man called light women the “Corvette” that will make others envy a man; all other women are like those regular cars no one wants. The light woman is the trophy. The segment’s conclusion was comedian-actor Chris Spencer telling a joke about how cute he is (so cute, in fact, that he doesn’t need a light woman on his arm). It seemed the goal was to make us laugh the painful segment away and to forget what had been said as black men divided sisters, who’d just shared the pain of their color journey — one saying her light skin has led to men assaulting her on numerous occasions — into cows and cars set for selection.

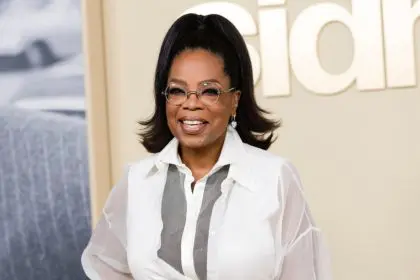

But I didn’t forget the segment’s sting. It was “doo-doo girls” all over again. I was pained. I was gutted again. I’d been traumatized again. And by my brothers. But that wasn’t what made it so bad. The worst part of the altercation was that it happened in my fairy godmother Oprah’s metaphorical house — OWN. You don’t show up on your fairy godmother’s doorstep expecting this kind of nonsensical discussion to occur without another sister elder — cue Toni Morrison — showing up with her wrinkled cinnamon-colored finger pointed at his forehead telling him to get up from the table and get out. Moreover, OWN, for me is supposed to be a safe space where such programming doesn’t get through. Where I wouldn’t have to wonder, “Did my fairy godmother even see this? Does she know this hurts? Does she realize there was no conclusion to restore my faith?” and then take to Facebook hoping to dialogue with other sisters to get the stink off of me and posting an angry message that would rack up likes and comments as the fire in Oprah’s house grew and grew around us. Apparently, most of my sisters, light and dark, were equally offended by the segment … and let down by the perpetrators and gatekeeper. One of my seasoned sorors of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Incorporated, retired school teacher Sandra Howell wrote on my post, “If my sons had ever come out their mouths with the crap y’all talking about, they would be wearing their mouths on the other side of their heads.” Right then I wished soror Howell was the CEO of OWN. That she’d been the gatekeeper for “Light Girls.”

I didn’t realize I would be writing about this documentary today. I went to bed happy I spoke my part on social media. It was enough to allow me to get some sleep. But when I woke up, I checked my Facebook inbox and there was a message from my interviewer, Shelia Moses, saying we needed to catch up. I hope she’s ready for another long conversation. I hope she is preparing to do a “Light Girls” book, but I hope it features in there somewhere a thoughtful conclusion I never got while watching the actual program.