“Great morning!” Divine says during our recent telephone interview.

His energy is infectious. I return his good humor and share with him my delight to have this interview. This writer came to know of Divine’s story through friends who are avid tech fans and later through online articles.

His foray in the tech community happened when he made a cyber shout-out to billionaire tech venture capitalist Ben Horowitz, co-founder of top-tier Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) on Twitter. Both fans of hip-hop, the two were fast friends. Horowitz and his wife Felicia pledged to Divine’s Kickstarter project for Divine’s debut album Ghetto Rhymin’. Divine’s tribute song and video to Ben, “Venture Capitalist (Like Ben Horowitz)” would follow, along with numerous articles written about their “unlikely friendship” appearing on such tech websites as TechCrunch SF, Tech Cocktail and Valleywag.

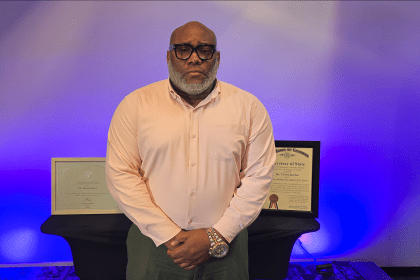

Divine’s fame continued to rise and he became the subject of a three-part Q-and-A article with Will Hayes, CEO of Lucidworks, for Forbes concerning diversity and inclusion in tech. He’s now a professional motivational inspirer, a unique term he coined, via his own 4th Letter Media company. He uses his extraordinary life story and journey to motivate and inspire others and assist in solving the problem of diversity and inclusion in tech.

Divine has a checkered past that has shaped him for this future. He’s relentless and ambitious, and more important, he doesn’t shy away from the grind and the hustle necessary to make it as an entrepreneur.

“My story is one of a young child who had a great life in the early stages and looked at the world through rose-colored lenses. Everything was beautiful to me as a child growing up,” shares the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based rap artist turned techpreneur.

By the time Divine reached age 10, his life “abruptly changed.” His mother and father had an unfortunate situation, which led to her emotional and mental breakdown. It’s when Divine met poverty and struggle head-on. “I never knew these social ills existed until they happened,” he shares. “My story ends up being one of determination, ambition, perseverance, resilience and redemption.”

Divine grew up in a home where his mom was really strict; she had “high morals.” It was during the ’80s crack epidemic that his young mother became a victim; she used crack cocaine.

“That set my life on a negative trajectory. To provide food, clothing and shelter for me and my younger brother, I started selling drugs. I was determined to succeed at that level because I wanted to get out of poverty and out of the situation of negativity and free my mom from her addiction,” he explains.

His determination to succeed — get money to survive and to change his life — came at a cost. At 19, he was incarcerated and sent to federal prison for manufacturing and distribution of drugs. He sold cocaine and crack.

“They sent me away for 84 months, seven years of my life. During that time, I became determined, with a new passion, to succeed and elevate [my] mind and spirit. Spirituality helped me through that time and I became determined to be a hip-hop recording artist and started studying the music from A to Z during my incarceration,” he remembers. “I did a lot of reading and didn’t focus too much on TV or radio and tried to be the best I could be while incarcerated and prepare for my release.”

He is currently working on his first book, Tweet Out Into The Ether: From Crack To Rap To Tech, a title he says was partly inspired by Felicia’s speech delivered at GLIDE Memorial Church in San Francisco about his life. Divine is also working on his first tech project, a product in the financial technology space. He is the CEO and founder of BLAK Fintech, which is an online and mobile financial services company that builds tech-driven personal financial and banking products for those in underserved urban communities for financial inclusion via the BLAK Card.

Get to know Divine.

What books did you read while incarcerated?

African American history books and the most impactful were The Autobiography of Malcolm X and The Black Muslims in America by C. Eric Lincoln. Books by Na’im Akbar; J.A. Rogers’ 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro; George G.M. James’ Stolen Legacy; Carter G. Woodson’s The Mis-Education of the Negro; Frances Cress Welsing’s The Isis Papers. The books about African American empowerment, Black knowledge and history proliferated in the prison system.

I read All You Need to Know About the Music Business by Donald S. Passman. It was a very good book and gave me knowledge about the music industry. Not only was I preparing as an artist by writing music, I was preparing to be an executive and start my label. That’s exactly what I did upon my release.

If you’d read those books sooner, do you think it would have made a difference in your life?

That’s interesting. When I first came into Black empowerment, Black and African American history at a high level, I was incarcerated in a juvenile facility. I started reading about it. When I was released, I was on the path of Black consciousness. However, I was in New York City purchasing high quantities of drugs. I would go to Spanish Harlem, 171st and Amsterdam to purchase drugs and then I would go to 125th Street in Harlem and purchase Black history books. It was a weird dynamic and process. I was doing one to survive, in a negative way, while conscious and trying to change my life, in a positive way, by gaining knowledge concerning the plight of Black people and African Americans in America.

I was out from the juvenile facility only six months when I was arrested on the federal charges. That’s when while re-incarcerated came in tune. Those books made the difference in my life and were the push I needed to get back to the past of wanting to live a certain way when I came home. I realized there were some things psychologically I had to battle and confront, and essentially break free of.

What does it do to your psyche to forever bear the label “felon?”

It reminds me of my past ways and criminal actions. It reminds me of my mistakes and errors in life, making adult decisions while still a child, a teenager. It doesn’t matter that I paid my debt to society with my incarceration. It brings me back to feeling inadequate, helpless and hopeless; it brings back those emotions.

When I came home, I was feeling very depressed. I’d lost a lot of friends and family whom I thought cared and loved me. Early on, it was a real struggle to overcome. I went back and forth to jail dealing with recidivism for years.

It wasn’t until this last incarceration five years ago that I really decided I wanted to break free from the psychological cell that I was locked in, being someone who relied on the selling of narcotics and criminal activity to survive and maintain.

What contributed to your breakthrough?

I have to say this. And I think I get criticized for it. Meeting Ben Horowitz is what shifted everything in me. It gave me the motivation, the inspiration and 100 percent dissatisfaction of living a criminal life. When I met him and his wife [Felicia] who were gracious enough to fly me out to California to spend time with him, that experience moving forward eventually gave me the courage and empowered me to finally break free of the psychological tendency and negative cycle of relying on criminal activity, selling drugs to survive. It’s not like they handed me money. They opened a door for me and showed me a whole new world. I met him in 2014. Ever since then I made the transition to cease the criminal activity and now no longer engage in it. I am proud of that. I am blessed. He gave me an opportunity.

I studied hard and I am determined to make it. I asked him to be my mentor. He told me he wanted to help me to bless the world. I am not Nas. I am not Kanye West. I really don’t have anything to give him in return. It’s the energy, love and humanity. Hip-hop brought us together. I will always sing Ben and Felicia’s praises.