Walter Cronkite was as much a part of my childhood as Big Bird and Mr. Rogers. The evening news was a staple in our home. My parents listened to the broadcast while reading, setting the table for dinner, or making sure homework was getting done. For some reason, the casual manner with which my parents watched the news made me feel safe. It was as if whatever was going on in the world was trapped inside our television, and once the television was turned off, the world’s problems disappeared. I remember when that magic trick no longer worked.

Each night there seemed to be a different Black child’s face and name on the screen. Black children, who were close to my age, were being killed in Atlanta, and according to the news, no one knew why. My parents were not just listening to this news; they were watching attentively. I saw the concern on their faces. The Atlanta Child Murders escaped the television and entered our home.

My parents were born and raised Colored in the Jim Crow South. Being Colored in the Jim Crow South meant that White folks had the power to exploit, rape, and murder Black folks, so Black children being killed in the deep South was not something new to my parents.

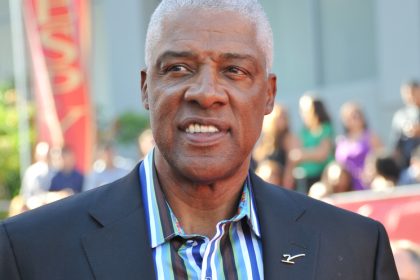

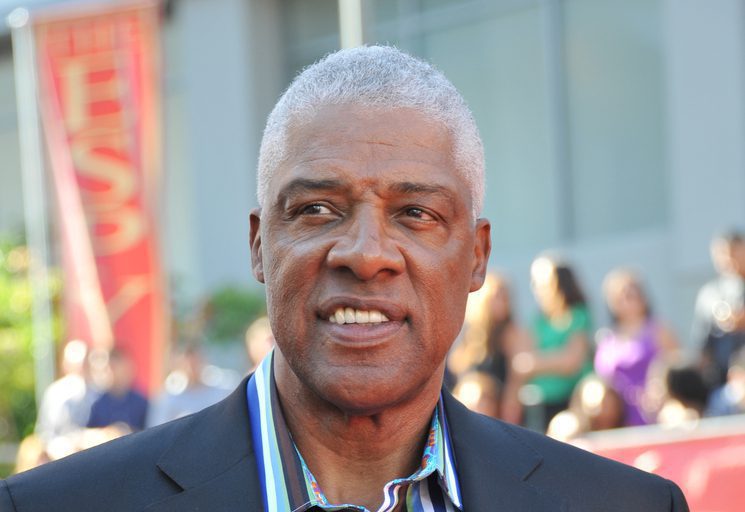

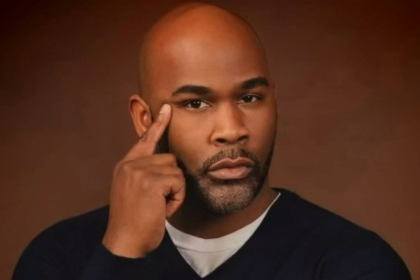

After putting her hand on my head, my Mom told my Dad to get my hair cut. I was trying to get a Dr. J afro, but Mom was more concerned with me looking decent for school pictures.

I loved going to the barbershop with my Dad. There was no subject that was off-limits, and nobody censored themselves because children were present. As I waited for Mr. Johnson to cut my hair, there was only one topic of conversation: The Atlanta Child Murders.

“They know it’s the Klan killing those damn kids,” an enraged Mr. Johnson shouted.

“Hey, that could happen right here in Albany, New York, too. They got Klan here,” chimed in the man whose hair Mr. Johnson was cutting.

“Hell, Irving, one of those kids could have been Sam,” Mr. Johnson said nonchalantly.

I felt my Dad’s discomfort with that remark, so I was shocked he did not respond to Mr. Johnson’s comment. On our way home, I understood why he remained silent.

I knew my Dad did not want to tell me what he was about to say, but he knew I had to hear it.

“Your Mom and I can teach you to fight racism, but we can’t protect you from it. Do you understand? It is important that you understand this.”

I nodded my head. That was the lesson. That was the end of my innocence.