Robyn Autry, Wesleyan University

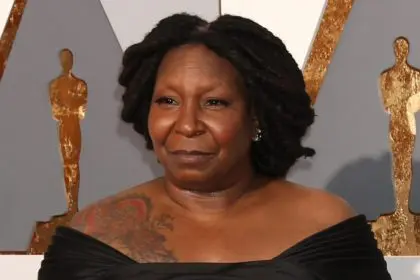

Whoopi Goldberg, co-host of ABC’s “The View,” set off a firestorm when she insisted on Jan. 31, 2022 that the Holocaust was “not about race.” Hands outstretched, she went on to describe the genocide as a conflict between “two white groups of people.”

As someone who writes and teaches about racial identity, I was struck by the firmness of Goldberg’s initial claim, her clumsy retraction and apologies, and the heated public reactions.

Her apology tour on her own show the next day, on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” and on Twitter

raised more questions about her views on race, antisemitism and the Holocaust. Goldberg also seemed unaware of the non-Jewish victims of the Nazis. By the end of the week, the president of ABC News described Goldberg’s remarks as “wrong and hurtful” and announced that she was suspended from the show for two weeks.

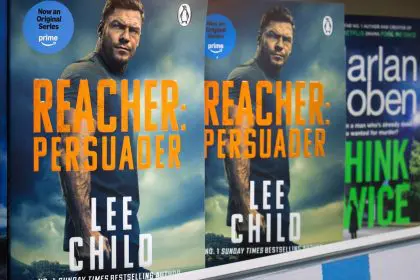

How did a conversation about the controversial banning of the Holocaust graphic book “Maus” by the Tennessee Board of Education, which Goldberg opposed, turn into such a media spectacle? And what does it tell us about the social norms guiding how we talk about race and violence?

Filling the void

Sociologist and American Civil Liberties Union attorney Jonathan Markovitz defines “racial spectacles” as mass media events surrounding some racial incident that is passionately debated before dying down.

Think of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee or Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s apology to the Cherokee Nation after taking a DNA test. Markovitz argues that the lack of ongoing public conversation about racism fuels these events, leaving Americans to react intermittently to shocking violence and salacious confessions. While it’s not bad that these events get people talking about race and racism, Markovitz worries that what is learned is limited because emotions tend to run high and these moments quickly fade from the news cycle.

In the absence of sustained national dialogue, shows like “The View” and comedians like Goldberg can easily become lightning rods. The American public often overestimates their ability to unpack complicated social issues. Are they public intellectuals or entertainers? Critics might also ask why someone like Goldberg, who has already demonstrated odd thinking about racial identity and a willingness to defend racist acts, would have such a huge platform in the first place. But this isn’t just about Whoopi Goldberg.

Let’s clear up a few points: Race is an elastic social category, not a fixed biological one; Jewish identity and experience are not synonymous with whiteness; and Jewish people have historically been treated as a distinct racial group. The Holocaust was the systematic genocide of some 6 million Jews from 1941 to 1945, fueled by the Nazis’ belief that they were an inferior race. Other victims included Poles, Roma, gay men, lesbians and others.

The Holocaust is one of the most extreme and tragic examples of what sociologists Michel Omi and Howard Winant referred to as “racial projects.” In their work on racial formation, they used that term to describe how racial categories are formed, transformed and destroyed over time. In other words, the fact the Jewish people themselves may disagree over whether they are a racial or ethnic group does not undo their long history of being categorized and marginalized as such.

Still, it is unsurprising that an American, perhaps especially a Black one like Goldberg or myself, would think that race is about skin color given how it plays out in our lives. As a graduate student studying racial violence and collective memory, I was stunned to learn how ideas about racial difference varied wildly across societies and how those ideas could morph within the same society over time.

I learned that race is a social idea that is propped up by observable traits, only one of which is skin color. The racialization of Jewish people may not be about complexion, but physical markers are still often used to differentiate and stereotype the Jewish body.

[Interested in science headlines but not politics? Or just politics or religion? The Conversation has newsletters to suit your interests.]

It is also important to understand ongoing antisemitism in the U.S. and efforts to deny that the Holocaust even happened. Goldberg’s remarks were clearly the sort of “excitable speech” that gender theorist Judith Butler writes about, disorienting us by bringing violent histories to bear on us today. The way we talk about the past matters – as does the way people are held accountable for misrepresenting it – because so much of it helps to explain the contours of existing conflict.

Another lesson

At the same time, dismissing Goldberg’s comments and the backlash would mean missing an opportunity to appreciate what can result. For example, in light of the recent controversy, the Anti-Defamation League announced it will revise its definition of racism to include both race and ethnicity.

In this moment, people are talking about Jewish identity, racism and a violent history we’re meant to “never forget.” But they’re also talking about Blackness.

What can we make of the frenzied rush to chastise and publicly ridicule a Black woman for talking about race in the wrong way? On the one hand, this is similar to other celebrities condemned for racist speech whose apologies get scrutinized.

Yet, the Goldberg affair feels different to me. It reignites a recurring suspicion that Black people, while oppressed, suffer from twisted bigoted racial thinking – that Black people are not innocent victims after all. When a Black celebrity makes racist remarks, suspicions reawaken that perhaps it is a collective failing. This sort of projection of individual acts onto an entire group as if it were a shared trait is anti-Black.

Yes, many of us think Goldberg got it horribly wrong. And yes, her apologies made matters worse. There are better ways to think and talk about race and racism.

But observers shouldn’t be surprised when these conversations go awry, considering how little time is spent openly having them in the first place.![]()

Robyn Autry, Associate Professor of Sociology, Wesleyan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.