Authors Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa, a pair of Washington Post reporters, wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning book about George Floyd. They went to a high school near Memphis to discuss and disseminate it. That’s where the controversy started.

The authors say they were prohibited from discussing systemic racism, one of the underlying themes of His Name is George Floyd because it is key to understanding why Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in May 2020.

The school system that invited them denies that it issued any such restriction.

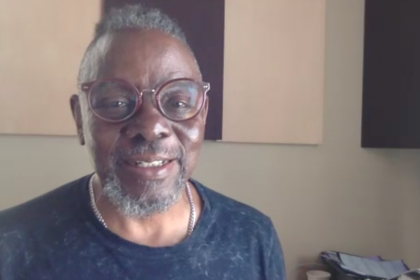

“It was really disappointing to hear that our speech was going to be limited,” said Olorunnipa, according to thegrio.com. “Not only for us but for the students whose access to knowledge is going to shape their journey in this world and this country.”

Cathryn Stout, a spokesperson for Memphis-Shelby County Schools, countered that the whole thing was a “miscommunication.” She said the issue was the book distribution during the event, which required a lengthy review process to comply with state and district regulations.

“Memphis-Shelby County Schools did not send any messaging that said the authors could not read an excerpt from the book,” Stout said. “Memphis-Shelby County Schools also did not send any messaging that said the authors could not discuss systematic racism or topics related to the death of George Floyd.”

Whether it was a miscommunication or not, this episode has become the most publicized test of Tennessee’s Age-Appropriate Materials Act. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee signed it into law last year, and it requires public schools to review library books to ensure they contain “materials appropriate for the age and maturity levels of the students who may access the materials, and that it is suitable for and consistent with, the educational mission of the school.”

It also prohibits teaching about racial and sexual inequality and privilege, and schools that ignore it could lose school funding from the state.

Free-speech proponents who are critical of the law — and others like it in states like Florida, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah — say it is being twisted in such a way as to whitewash history. Under the provisions of the law, which they complain are vague, the Jan. 6 U.S. Capitol riots or the police killings of Black men and subsequent protests in 2020 could not be covered in history lessons.

It’s the very thing that Samuels and Olorunnipa argue they were “blindsided” by when they were set to discuss their book at Whitehaven High, a predominantly Black school.

“I thought about my personal disappointment and feelings of naïveté that despite all the work Tolu and I had done to make sure the book would be written in a way that was accessible to them, a larger system decided that they were going to take it away,” Samuels said according to NBC.

Every year, Memphis Reads, the event organizers, picks a book that “engages Memphians in issues that are relative to daily societal topics and themes.” The group apologized for its role in bringing the authors and the school together. Justin Brooks, the university’s Center for Community Engagement director involved in planning the event, relayed the restrictions to the authors without direct communication from the school district.

In response, Samuels and Olorunnipa say they plan to provide Whitehaven students with copies of their book through an external local organization, circumventing the school system’s limitations.