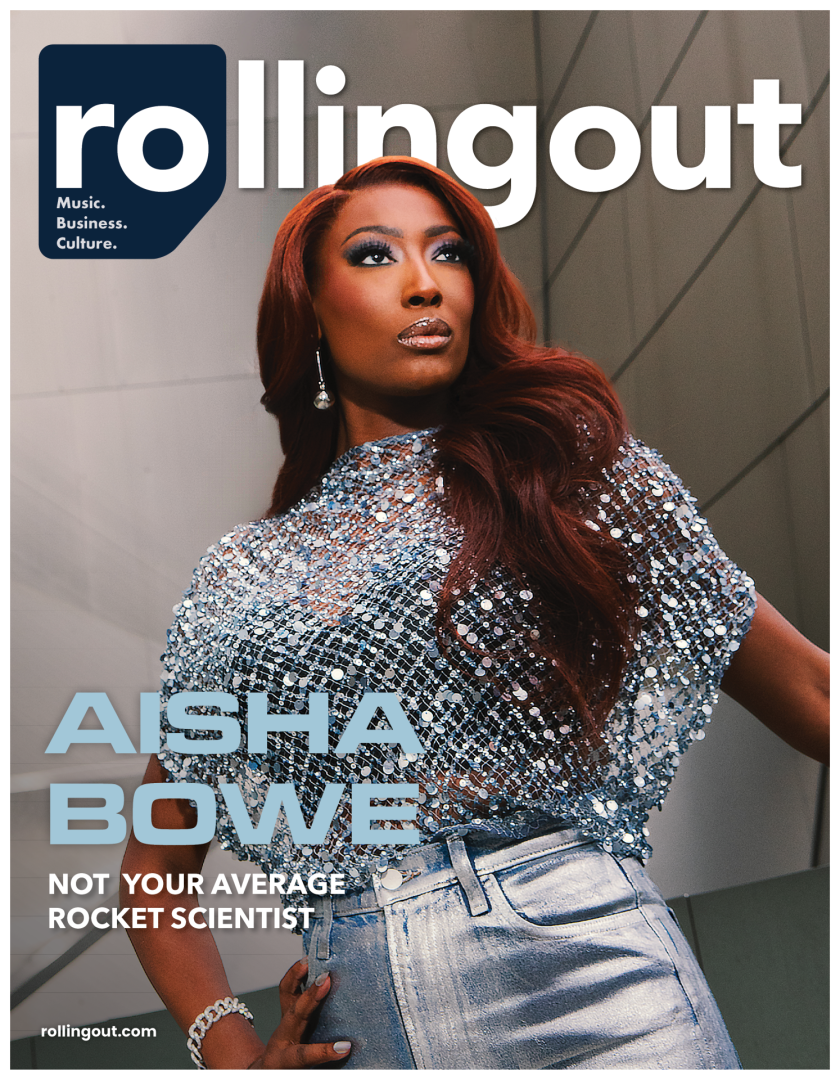

From being told to settle for cosmetology by a high school guidance counselor to launching into space as part of Blue Origin’s all-female NS-31 crew, Aisha Bowe’s journey is a masterclass in rewriting the rules. The aerospace engineer, entrepreneur, and commercial astronaut has built her career on defying expectations and creating her own opportunities.

For the space mission, she handpicked an HBCU experiment to take with her, trained for years and raised the funding for her seat — all while carrying the dreams of young people, who rarely see themselves represented, among the stars.

Now, she sits down with rolling out to share why she is making space literally and figuratively.

When did you become fascinated with space?

Growing up, I loved books and science fiction, but space never felt like an option for a kid like me. It seemed like a dream reserved for other people’s kids. Those with stable homes and support systems, not someone who didn’t even apply to college in high school because of a guidance counselor’s discouragement.

Falling in love with space came later, when I realized no one else gets to define me, my life, or my success. It took years of showing up, learning how to believe in myself, and outworking every doubt I had. That journey turned space from an impossible dream into something I knew I could claim for myself.

You spent six years at NASA but left to found your own companies. What inspired you to leave and take on the challenge of building STEMBoard and LINGO?

I loved working at NASA, the experience shaped me as a rocket scientist. But after six years, I wanted a new challenge. I had met founders who were solving problems in bold, unconventional ways, and I started wondering: What if I could build something of my own, too?

That’s how STEMBoard started. Over more than a decade, it has grown into an award-winning engineering firm, recognized by Inc. Magazine and named one of the best women-owned businesses in the country.

But I knew real impact meant reaching back even further. That’s why I created LINGO, a hands-on, project-based STEM kit that makes coding and engineering fun and accessible for kids who might not otherwise see themselves in tech. As we set out to grow the company, I became one of fewer than 2 percent of women founders to raise over a million in venture capital. Now, we’re on a mission to equip 1 million learners with real STEM skills because those skills are how we change who gets to lead in this industry.

With so much accomplished, why space and why now?

After more than a decade running my company, I looked around and asked myself: Why are we still so underrepresented in this field? I’ve seen firsthand how powerful it is when people can see someone who looks like them doing something they never thought was possible. Visibility changes what people believe is possible for themselves. I felt an urgency to help make that visible right now, not someday.

In 2022, I started working toward this goal in silence. I read the federal spaceflight regulations, created a training plan, talked to experts, and slowly began to figure it out. I didn’t know exactly how I was going to make it happen at first, but I was determined. So I chose an experiment with an HBCU, raised the money myself, trained for two years, and flew as part of Blue Origin’s historic all-female NS-31 crew.

What’s a principle that you live by when it comes to becoming a scientist that you would want to see within the Black community?

One principle I live by is simple: If someone tells you that you can’t do something, do it anyway because one day they’ll claim they always knew you could. Too many of us carry the weight of other people’s assumptions about what we can or can’t be. I know I did. Early on, I spent more time questioning myself than I did questioning the world around me. Once I flipped that, everything changed.

I went from graduating high school with a 2.3 GPA, being told I wouldn’t get into college, wouldn’t work at NASA, wouldn’t run my own company, wouldn’t raise venture capital, and definitely wouldn’t go to space. I did all of that anyway.

So, the principle I want everyone to take away, especially in our community, is: You have to try. You have to do. Because once you do, you’ll realize that what you thought was impossible is absolutely within reach.

If you were giving a speech at Spelman or Howard, how would you describe some opportunities in space that our community doesn’t hear about enough?

When I worked at NASA, the idea of flying to space as a commercial passenger didn’t even exist. There was only one path: Become a career astronaut and compete for a handful of government slots. Companies like Blue Origin and SpaceX have changed all of that. Now, space is opening up in ways we’ve never seen before.

Many of today’s most successful space companies aren’t run just by engineers. They’re built by entrepreneurs, scientists, lawyers, and creatives who saw an opportunity and went for it. That’s why I tell students: We need everybody. We need space accountants, space lawyers, space doctors, designers, and policymakers. Every field can be a “space” field. So, if you’re curious, go for it. There’s no single path or roadmap; the only requirement is that you believe you belong.

Based on what you know, when it comes to the world of space and opportunities in this field, where do you think Black women such as yourself should take up the most space?

I want to see more Black women and Black people, period, leading in every part of the space industry. Not just as engineers or astronauts, but as researchers, policymakers, and decision-makers.

The more data we capture ethically and intentionally, the more we can design better outcomes with our communities in mind. For example, the health research we do in space doesn’t stay in orbit. It comes back to Earth as new technology: medical imaging breakthroughs, better diagnostics, and medical treatments that can save lives in our neighborhoods. Look at how mammogram technology and telehealth have roots in space innovation – that’s a direct line back to everyday people.

When I flew, I contributed biometric data to add more information about how African-American women’s bodies adapt to microgravity. This matters because it shapes future health care, equipment design, and even earth-based treatments. There’s so much room for us to shape what space means here at home.

Take us back to launch day. What did that morning mean to you, and what will you always remember about it?

By the time launch day arrived, I had been training for that moment since 2022. I’d flown fighter jets, jumped out of planes, and trained at the only FAA-approved human-rated centrifuge in the country, pulling 6Gs to prepare my body for the stress of spaceflight.

That morning started around 2 a.m. for me with lots of prayer and reflection. That day I was greeted by nearly every Black woman who has ever been to space: Dr. Mae Jemison, Joan Higginbotham, and Jeanette Epps, all NASA astronauts, along with Dr. Sian Proctor who flew with SpaceX, and Keisha Schahaff and Anastatia Mayers, the first mother-daughter duo to fly with Virgin Galactic.

Standing there with them felt bigger than just a launch. It was a reminder that representation builds bridges, and that each of us is proof to someone else that they belong, too.

And in that same moment, I saw my 93-year-old grandfather, a man born on a small island in the Bahamas (without airplanes) standing there to watch his granddaughter reach space. Seeing him, seeing my community of Black women astronauts, and knowing that kids everywhere would see this too … that was everything for me.

From the early morning suit-up to the walkout, I felt completely ready. It wasn’t just about me going to space. It was about carrying all of our stories and making sure I could continue to crack the door for someone else to walk through.

Photography by Tyreek Voltaire