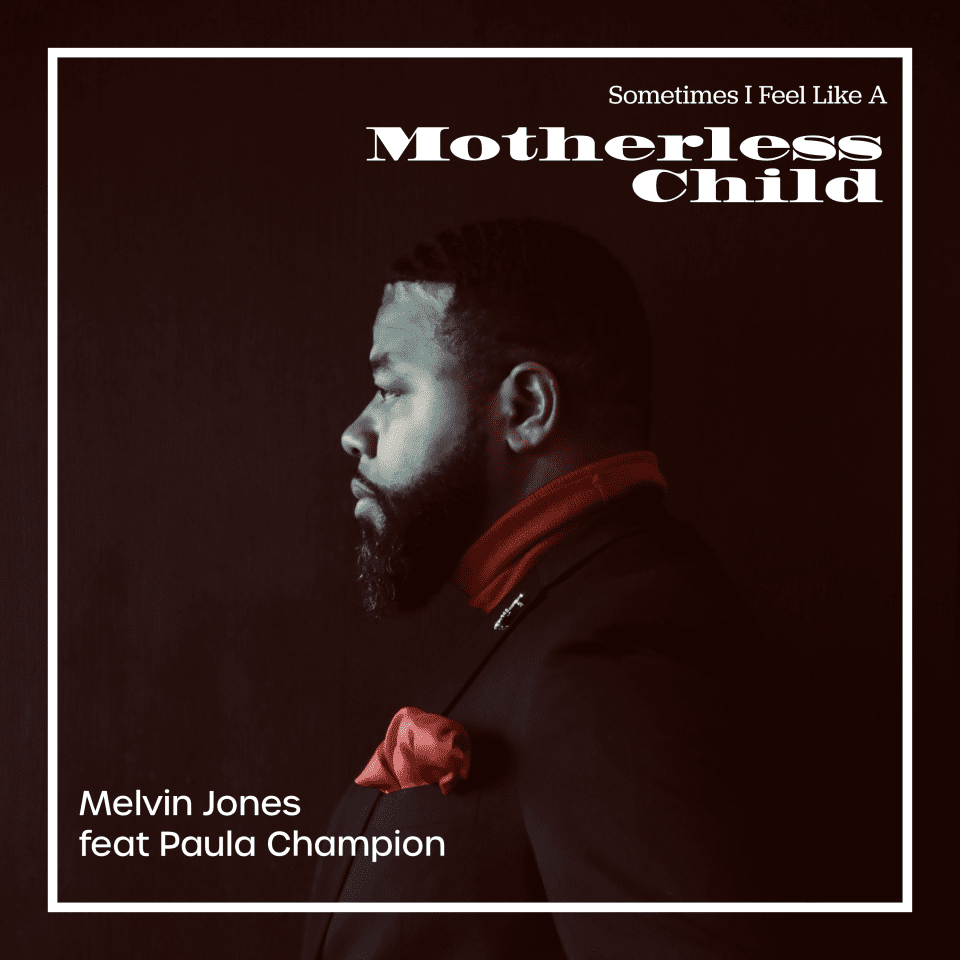

Memphis, Tennessee, native Melvin Jones made his professional recording debut in 1998, while enrolled at Morehouse College. He appeared on TLC’s triple-platinum hit “No Scrubs,” not knowing it would lead to his first Grammy. After graduating with honors from Morehouse, Jones went on to earn a master’s degree in music with honors from the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University. While at Rutgers, he received the intensive instruction of the late, world-renowned educator and trumpet impresario, William “Prof” Fielder, whose student roster includes such prolific figures as Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Sean Jones, and Terrell Stafford.

Following some high-profile work in the country’s northeastern region, Melvin dramatically slowed the pace of his performance career to accept the position as Director of Bands and Instrumental Studies for his alma mater Morehouse College. At age 24, “Mr. Jones” officially became the youngest full professor/ band director in the college’s history, and under his leadership the entire band program re-branded itself nationally as a powerhouse among HBCU programs.

Following years of service, Jones resigned from his position at Morehouse to resume full-time performance endeavors. Almost immediately, he began touring with Tyler Perry’s company on numerous stage productions and special events, which led to appearances on a dozen film and television productions on both sides of the camera.

Over the course of two decades, Melvin has toured, recorded, and/or performed extensively around the world with such artists as PJ Morton, Patti LaBelle, Illinois Jacquet, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Jennifer Holliday, Stevie Wonder, Arrested Development, The 21st Century Band, Young Jeezy, Marcus Roberts, The Anointed Pace Sisters, Missy Elliott, the Pussycat Dolls, Earth, Wind, & Fire, Jerry Douglas, Wycliffe Gordon, Gladys Knight, and the list goes on and on.

Jones’ career has been all over the map, having appeared on over 250 recordings, and performing in the house orchestras of multiple awards shows, talk shows, and on stages around the world.

Munson Steed: Hey, everybody! This is Munson Steed and welcome to Star studio, where you learn what it is to actually build and create stars and start them. I’m joined today, my dear brother Professor, a true mover of the music forward with superstars that literally have residencies around the world. It is my one and only brother, Melvin Jones. How are you?

Melvin Jones: I’m great, sir. How about yourself?

MS: I’m fantastic, but [for] those who don’t know much about what it is to teach music and then to support a mega superstar, give them an idea of your discography, and how you have been able to approach music as a professional?

MJ: Well, from a discography, I started in college at Morehouse, actually. My very first recording session was with TLC. So, it became a hit, No Scrubs, and that gave me the first professional experience to let me know that this was something I could do as a viable career. And since then, the career has taken me to five of the seven continents and I’ve had an opportunity to appear on over 200 or so recordings. Also TV shows, movies, some of the soundtrack work behind the scenes. Currently, I am a part of Usher’s band. We just finished our Las Vegas Residency, and after the Residency we ended up doing a lot of really amazing things with Usher overseas and as well as recording a music video or two.

And now, we are prepping for his world tour after just completing the Super Bowl, which was a lot of fun. And outside of my association with Usher, I also work with a music producer named Adam Blackstone, whose hands are in literally everything under the sun. He’s also the way that I was connected with Usher and with him. You can hear me a lot more than you see me, as I had the opportunity to record a lot of the things that he’s involved with, including the melody of the premier of “The Wiz” just came out this past week up in the city. Also, Alicia Keys has a fantastic production out, had a really teeny part play in that, thanks to Brother Blackstone, and so many other like milestones, that I can’t even name the highlight reel at this point. It’s ever-expanding.

MS: So, when you think about collaboration as an artist, how important is collaboration to creativity?

MJ: Oh, it’s of the utmost importance. Because what you find is, there’s almost nothing that you can do, in which you cover everything from the beginning to the end. There have to be other hands involved, and I always laugh when I hear people say that they are self-made, or that they did it all on their own. That’s impossible. It doesn’t work that way. I mean, even if you may have had your hands in every element of creation, the only way somebody is gonna even hear that creation, is if somebody else’s hands are involved. So, collaboration and the relationships that come from doing this are, I think, equally as important as the field that you build up.

MS: When you are literally in the studio with a star, and someone comes to you, what are you looking to do when they’re asking for your input on making something hot, like when they’re asking you what you hear?

MJ: It’s a funny balance, because you have to read the room. When it comes to certain artists, you have to know how much of you they want, or how much of them they want to hear in your voice. It’s a really interesting thing, and I love being in a room with artists who really have a sense of what they want. And so, when they give me that, and then give me freedom to expound on it. That’s a completely different process, whereas a lot of times, I’ll be in situations where they’ll bring me to the table because they want to know. Well, what can you add to this? So, we know that we want the elements that you provide. We just need some detail now. We want you to fill in these blanks. So, it’s just really a case-by-case situation.

MS: And so, you’ve had the opportunity to both be in residency with per se, an Usher, and then yet be in the beginning of what is a phenomenal run with TLC. All of that’s coming out of LaFace records. And [what do] you think about LaFace, and its real effect on the music business and how it impacted Atlanta?

MJ: Well, so when you mentioned LaFace is a funny thing, because when I was in school, when we did the TLC thing. That’s when they had the physical brick-and-mortar spot over in Buckhead and it’s my first time getting a chance doing that recording. I was a sophomore in college and had no idea of what the industry itself entailed. I just like playing the trumpet, and that, I had a lot of opportunities up until then. That’s my first real opportunity to see the full scope of the business.

What LaFace does, and what a place like that does in general for the musical environment is, it helps, how to put it? Like Atlanta, it is already a draw for the arts in general, and music. Well, LaFace does provide a landing pad, a kind of a melting pot for that, and in turn, because it’s here, you get a wider variety, and even a larger scope of artists that come to town. So, they spread that to the rest of the scene, something like that the way it affects the entire musical ecosystem.

That’s when you have certain clubs that are now available. Those clubs that really value the aspect of live entertainment and what it takes to bring people into the doors. That also changes the restaurant industry. It’s kind of a domino effect, something like LaFace here, during those years. There was an overabundance of clubs and performance opportunities of every single style of music.

You could go out to a jam session and play R&B. There was the underground Hip-hop Club. There was a host of straight-ahead jazz clubs as well, the smooth kind of smooth jazz clubs, rough jazz clubs if you would. Whatever the case, whatever you were looking for, there was a place for you to express that, be in a community of other people that share that expression. And at some point the record producers would take a step or dip their toes into those waters, and those would be the elements that go into creating the music that eventually came out of LaFace.

So, I think something like that is super important again to the musical ecosystem if you want to see creativity. That’s the way to have it, is to have some kind of central hub to kind of bring the people together.

MS: When you think about your voice, how would you describe your voice as a trumpeter? Because most people will think of my two favorites, obviously Satchmo [Louis Armstrong] — truly my favorite trumpeter, but he was so much more, could sing, the presence as a leading man — and then, obviously the guy who really just didn’t care and wanted to push the trumpet to a whole electric sound, Miles [Davis].

MJ: Yeah.

MS: Where are you? When you think about how you put and obviously celebrate all the men? Not taking anything from our dear brother Wynton [Marsalis], or any of the others, Terence Blanchard.

MJ: Yeah.

MS: Guys like that who kind of paved even that road. While you were in college on your Morehouse brother, Spike Lee, “Mo’ Better Blues.”

MJ: Yeah.

MS: Where are those guys who’s really putting that together, as you kind of like, define what you are to the universe?

MJ: Well, for me it’s an interesting thing, because jazz is my first love, and when it comes to the instrument itself, when it comes to the music, and if you study jazz, if you study it intently, all roads will ultimately lead you right back to Louis Armstrong. There’s no way to get away from that. You’re listening to the music. You’re listening to a piece of Batman’s legacy and especially in a modern sense. So, when you start naming all of the people that come out of that, the branches out, especially the New Orleans tradition.

I feel like that is a chapter of trumpet. It’s a very necessary chapter, because a lot of the things that go into these other styles of music did originate in jazz, did come from those styles where you branch off and get things along the lines of R&B, and some of the more modern versions. Country is a lot of things that go into gospel. So, when we talk about my individual voice the way I see it, my life has been kind of a musical melting pot of its own. I grew up in Memphis, Tennessee. Everyone knows it as the home of the blues.

When I was growing up, in a time that hip-hop was king, or like underground rap. So, I grew up with that in the beginning, and then we have the music that my parents listen to, takes us back to Earth, Wind & Fire, Michael Jackson, Prince. This is a combination of artists there and coming to Atlanta from that environment, I just got a taste of everything. By the time I got to Morehouse, this is when I realized that the word Black was an umbrella term describing it. Now we had Black men from every corner of the earth, bringing their culture and bringing their map together, and all of that came together to play a part in the stuff that I felt the exposure.

But I feel that the exposure to those things really transformed the way I heard music, and in turn the way I wanted to perform music. But when I listen to the things that I do now, I was just checking out a bunch of recording sessions that I’ve done over the past two or three weeks, and it runs the gamut from gospel, to country, to traditional gospel, to new-page gospel, hip-hop. It’s just a lot that’s happened in the last few weeks, and I feel like the ability to genuinely feel and represent that music is what goes into my ability to contribute to those different styles of music. I know it’s kind of a long way to get there. Yeah.

MS: But when you think about that, it sounds a little bit like your other Morehouse brother, when you hear his voice and it could be Jojo over here and the next thing he has it. But how would you describe you and P.J.?

MJ: Wow!

MS: And the other Morehouse men. Come in on down there. How you guys are kind of approaching, not leaving any faith or behind, but really giving faith a different face, and yet still saying, there’s a love, for there’s God in all music. If you just listen a little bit.

MJ: Well, I mean, that’s the fact. I mean, that’s the first identifiable style of music that we can say we contributed to the world from this particular continent. And if you came through Morehouse, if you went through the full program of going from the beginning of starting off as a man of Morehouse, company of Morehouse men. If you went through that matriculation, then you have a much deeper appreciation for what you contribute to the world scale. So, in terms of music, P.J. and I work together, like we actually had this conversation.

What Morehouse does is assign a different level of responsibility to what you put out there. You can decide to be a musician, but if you’re gonna do it. It has to mean something different, because somebody is watching you that you have no idea about, and the things that you do, the way that you do them ultimately impact what they may do. And Morehouse puts you in a position where you learn to accept that particular responsibility and wear it with pride.

So when, we have decided to go into this particular industry, when you listen to P.J.’s music. What you hear is a much more realistic sense of where religion falls in real life. Because I think a lot of the time, I’ve come across a lot of, I won’t say overly religious people, but unrealistically religious people. People who may not have even read the very book that they’re claiming to be the center of their particular faith, and when it comes time to apply that stuff. They are dead in the water, because they read up on it so much that they don’t even see it when it’s happening in front of them.

And so, when you’re really in this world, when you’re really a part of it, as this industry push you. You deal with every single side of the coin with every walk of life, and if you are not comfortable enough with the way you’re supposed to treat people in general. Then you’re setting yourself up to fail in this particular community, because whatever you dislike, you’re going to end up working with or they’re gonna call you, or they’re not gonna call you. They’re gonna be your boss or they’re not gonna be your boss.

That’s the deal with this. So, you really put it into faith and I tell people all the time there’s never been a greater test to faith than being an entrepreneur, than being a musician, than being an artist, because you start every single month off at zero. And you just know it’s gonna work. Boom!

MS: When you say that, and you are doing residency with a superstar. How’s it feel that growth? Between, I was just in the room with TLC and I got a piece. I got a touch of a start and took off and now I’m with somebody that there’s no question around the world that this is a star. For the young brothers, who are really wondering if this is something they want to do, how do you suggest they best prepare? So that when they do have these opportunities as professionals, they can still stay in the room versus be put out of the room, because you don’t fit?

MJ: Well, I see three points in there that I always end up sharing with my students, and anytime I do master classes of this effect. Point No. 1, you’re going to have to perfect your particular craft. But that doesn’t mean — and I have to be really clear with this with students — that doesn’t mean you have to be Wynton Marsalis. That doesn’t mean that you have to be Terence Blanchard, that means that you have to be the best version of what you are developing.

And in that, that’s when you start to get the notoriety, you don’t want people to remember, hey, there was somebody that I heard that other day that sounded like Wynton. You want them to know, Oh yeah, there was this Ted Melvin Jones really stood out, had his own thing going on. So, you develop your voice and there’s a lot of other musical technology, and terms, and techniques to get you there. First, you develop your voice, your medium, and you take it seriously, because every day that you spend not in the practice room. Your competition is in the practice room, that’s first.

Second off, you have to define success in your own way. Because I think people think success is money. They think it’s playing. They think it’s camera time, likes now, which is the thing that didn’t exist when I was younger. But whatever it is that you choose to make your beacon of success, then you have to follow that first, because it changes over time. Like for me, the idea of success is being able to say no. There’s a time in my career when I had to take everything that came on my plate, and the sacrifices that come with making those choices are just too much to count.

But the idea of getting to a position in which “No, I can’t do this particular thing, but thank you for calling me. I can suggest somebody.” That’s my measure of success. So, whatever that particular thing is, you have to make that into a tangible goal. Every goal has steps to get you there. And mine took me over 20 some years, but I’m happy with that particular process, and the last and most important thing. You just have to be a good person.

That is the hardest part, a lot of times the social aspect is different with this generation of musicians. Because their entire existence is at a distance. They’ll be right next to each other and still communicating on electronic devices. And so it’s a thing, you gotta get to the point where you can put that phone down, face down, and have a face-to-face conversation with somebody and not weird them out. I’ve been in a room with tons and tons of amazingly talented people who will never get the same calls as the less talented people, because of one or two little personality flaws that they never identified in themselves.

It’s like, “Oh, so and so is amazing but he plays with kitten calendars all day, I don’t really know how to take that.” And you mentioned earlier, the idea of these relationships, and how collaboration works. These tours and the residencies, and all of these things that we’re doing. What they end up being is a big hang, when it’s all said and done. You spend a total of an hour of a day on stage. That other 23 hours ends up being some sort of communication time between you and the people that you work with, and if you’re the weird person in the room, then the decision maker that’s in the room may not call you for that type of opportunity.

So, you just have to be a good person. You have to know how to deal with people, how to read the room appropriately. All of these normal things that we grew up learning on the streets. It seems like now you have to find a way with the younger generation to refine those skills away from electronic devices. That’s I think that’s the biggest challenge for them. ‘Cause I’ve met some really talented kids who can’t carry a conversation, and it makes me concerned for them. Like man, that may work on the ground but at some point you’re gonna have to be on stage or in a rehearsal, or in one of those long 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-hour sessions, where you sit next to somebody, and it’s gonna be about more than the instrument of your hand.

MS: Super. Well, I wanna thank you, Brother Jones, for giving us insight here at Star Studio. Congratulations on your continued success. Much love and very proud of my Morehouse brother. For you out there, listen to this, share it. Know that he is truly a genius in this business. Not only is he on tour, but he’s teaching and giving it back to the next generation. I’m Munson Steed here on Star Studio for rolling out, thank you man.

MJ: My brother. Thank you. Have a great one.