In Louisiana, Black communities are grappling with the harsh realities of systemic and environmental racism, particularly as the Gulf Coast witnesses the largest fossil fuel expansion in recent history. Currently, 28 methane export facilities are either proposed or under construction, while only seven are operational. This alarming trend is not isolated to Louisiana; it reflects a global pattern where 114 new regasification terminals are set to launch worldwide between 2024 and 2030. Despite these developments, the International Energy Agency has warned that there is no need for further fossil fuel expansion, urging an immediate halt to such projects.

The Impact of Methane Facilities

Major U.S. banking institutions heavily finance these methane facilities, and their presence has dire consequences for nearby residents, particularly in communities of color. Health issues are rampant in these areas.

In regions like “Cancer Alley,” a stretch of industrial facilities between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, methane-producing industries are exacerbating health problems for the predominantly Black and low-income residents living nearby. Long-term exposure to pollutants associated with methane facilities has been linked to respiratory issues, chronic headaches, dizziness, and other more severe conditions such as asthma, cardiovascular diseases, and even cancer.

Residents report increased health problems over the years as methane facilities have expanded. Flaring, a process where excess methane is burned off, releases toxic chemicals into the air, further contaminating local environments. Some communities have experienced constant exposure to these pollutants, resulting in concerns about the long-term impacts on both physical and mental health.

Moreover, children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of this pollution. Studies conducted in affected areas have shown higher rates of respiratory diseases and other ailments compared to areas without methane facilities.

Despite these concerns, regulation of methane emissions remains inconsistent, leaving many residents frustrated and feeling abandoned by regulatory bodies. Activists and local leaders continue to push for stricter enforcement of environmental regulations to protect public health, but the fight is ongoing as industries maintain significant political and economic influence in the region.

A Call to Action

During a recent forum at the start of Climate Week, Indigenous leaders and policymakers discussed the financial mechanisms that perpetuate climate injustices. To safeguard future generations and disrupt the cycle in which a select few benefit from the suffering of many, solutions must be backed by financial giants.

Although the Biden administration has initiated programs like the Justice 40 initiative and a pause on LNG/methane projects, banks have repeatedly failed to fulfill their promises to shift financing from fossil fuels to sustainable energy solutions.

As communities confront the challenges posed by environmental racism and climate change, it is essential to recognize that shutting down methane facilities benefits not only Gulf Coast communities but also people worldwide. The fight against these injustices is not just about local issues but a global struggle for equity and justice.

Community Leadership

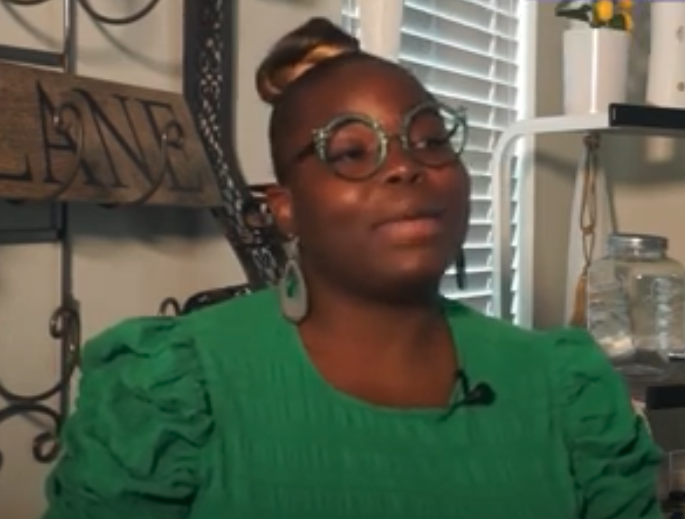

Roishetta Sibley Ozane, founder of the Vessel Project of Louisiana, emphasizes that the fight is not just for survival but for a future where all communities can thrive. As a fierce advocate for climate justice, she works to amplify the voices of frontline communities, particularly low-income and Black residents impacted by pollution and industrial expansion. Through the Vessel Project, Ozane provides direct aid and mutual support, ensuring that the fight against harmful industries and environmental degradation is also a fight for equity, dignity, and the basic human rights of affected communities. Beyond immediate relief, Ozane pushes for systemic change by fighting against the expansion of harmful industries, advocating for sustainable development, and empowering affected communities to take action. Her work bridges the gap between climate justice and social justice, ensuring that those most vulnerable are seen, heard, and supported.