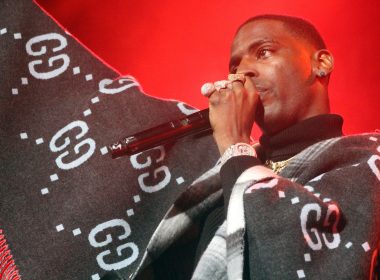

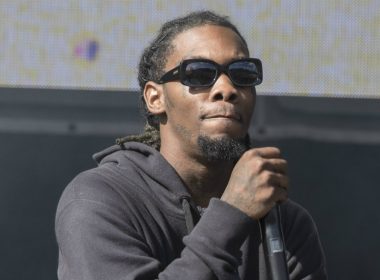

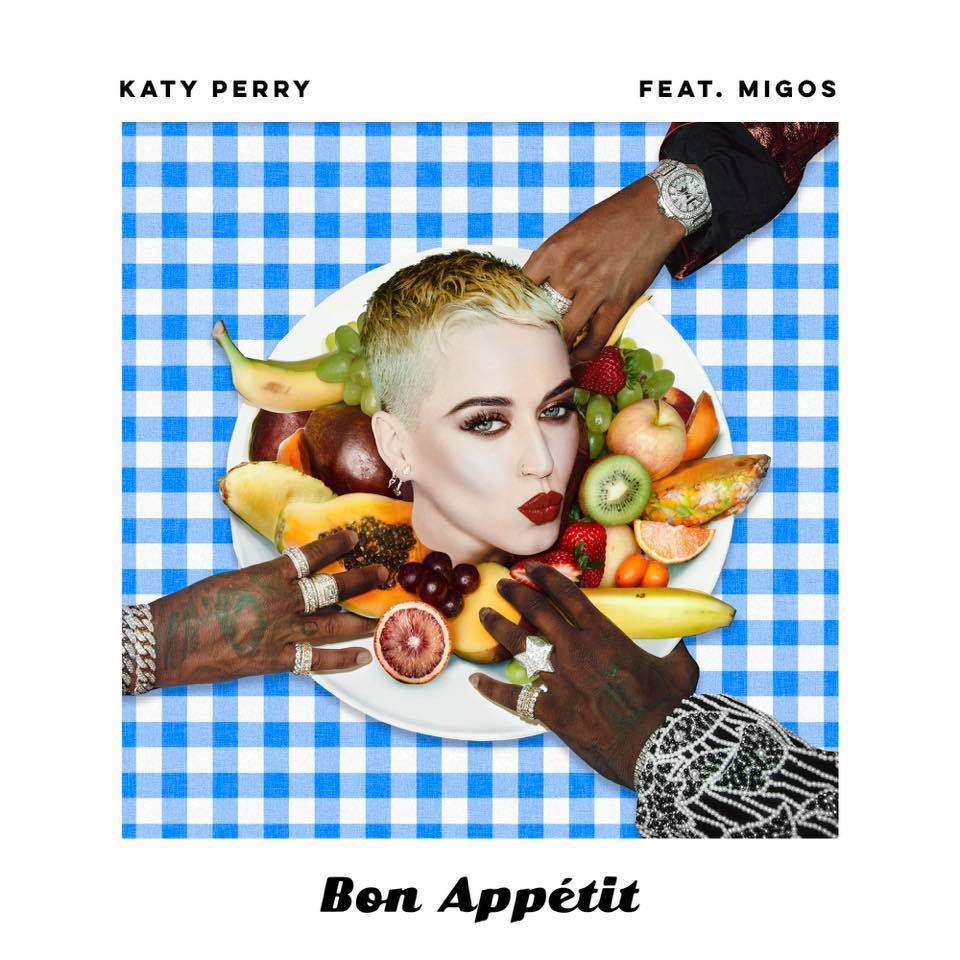

On May 20, 2017, Katy Perry performed her newest single “Bon Appétit” on “Saturday Night Live.” It was a pretty typical routine — nothing particularly surprising for an SNL performance from one of pop’s biggest singers. That was for the first two and a half minutes at least – after that it got weird. Here’s a short recap from after the 2:30 mark: Katy Perry finishes the second verse of the song, signaling that it’s time for a black guy, or in this case three of them, to rap for about 30 seconds – it is, after all, a Katy Perry song. Quavo starts and raps about sweet potato pie. Takeoff goes next, but Katy’s “dancing” and Miley v.2.0 haircut are too distracting to discern anything he says. Offset goes last. Perry lets off a classic “Offset!” shout that registers at about a 6.5 on the Cringe-worthiness Scale, then two seconds later lets off a couple of dabs (still unsure though) that move the scale from a 6.5 to around a nine. The song goes on for about 30 more seconds, then she gives Offset some fruit. He promptly throws it away, then the performance ends. As just a song and nothing else, “Bon Appétit” is another super sexual metaphor that will stay toward the top of the Hot 100 for a couple weeks. But, as a musical case study speaking to the state of pop and hip-hop in the current day, “Bon Appétit” is a lot more.

The underlying idea and structure behind “Bon Appétit” is nothing new. For years now, mainstream pop acts have been partnering with mainstream hip-hop acts in a way that could best be described as lacking severely in purpose. Not to say that pop as a genre has no room for hip-hop, or vice versa, but songs like “Payphone”, “Dark Horse,” and Perry’s other new single, “Swish, Swish,” are all the products of a formulaic production process that seems to treat rap as an afterthought. These songs charted well and are fun to listen to, sure, but it gets frustrating to always hear eight bars of rap appended to the tail-end of a new radio single by the same unimaginative artists in the same unimaginative ways. At best, this process churns out pleasant pop songs to be played on repeat at tween birthday parties everywhere. At worst, it represents a misunderstanding of the sheer depth of hip-hop and rap and functions as a blatant appropriation of Black culture.

Take an inventory of all of the most popular hip-hop artists and pop/rap collaborations from the past year or two. The mainstream chart success and widespread popularity that characterize this list reveal two things. First, that the contemporary understanding of trap music has gained an unbelievably strong following in current music and isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. And second, everyone outside of hip-hop wants a piece of the super profitable pie that is trap, but few can use the music properly once they get their hands on it. When Miley Cyrus gets her hands on the music, she appropriates the culture that it came from. When Maroon 5 gets their hands on it, they force unnecessary verses into their songs, serving as thinly veiled attempts to sell their music with a cheap new “coolness” factor. And when Katy Perry does it, she dances like an out-of-touch suburban parent and gets mercilessly roasted on Twitter.

So then, the question remains – what is the right way to use trap music, and more importantly, who is doing it correctly? I can’t lie – at this point, I’d much prefer to take the critical high road and assert that trap music isn’t a genre of music to simply be “used,” and even further, that artists like Maroon 5 and Katy Perry are doing the artists of trap an injustice by “using” the music’s ubiquity and culture for their own personal gain. The only problem is that a statement like that would be demonstrably false. In fact, trap music actually has a lot to gain from being associated with the likes of mainstream pop artists, no matter the artists’ intentions.

It’s a hard pill to swallow for hip-hop old heads and rap’s own SJWs, but the heyday of intense lyricism and dynamic storytelling is subsiding. Trap music used to be defined as the proverbial story of the come up, and it was articulated by some of hip-hop’s finest. But fast-forward 20 years, and somehow, trap music now is almost completely separated from the trap music of yesterday. Almost. Don’t be confused – at its core, trap still tells the story of the come up. RZA will tell you just as quickly as Miles McCollum will say it today: cash rules everything around us. The only difference is that now, artists are working smarter and not harder. 50 Cent and Jay-Z sold coke in the streets of Queens and Brooklyn. Lil Yachty became a celebrity Instagram personality before he graduated from high school and signs modeling contracts with Nautica. In the same vein, three unassuming guys from Atlanta’s Nawfside have an unmatched ability to make club and frat house bangers, and now, have a number one charting single with a person who was at one time music’s wealthiest woman. At the end of the day, trap music, just like life, is often about the monetary come up. But luckily for the artists, the come up has become a lot less gruesome.

Furthermore, changes to a genre as popular as rap cannot exist in a vacuum. If trap artists get to make music that’s solely about having fun, making money, and being from the bustling cultural mecca that is Atlanta, then it makes sense that pop artists will jump at any and every opportunity to associate their names with these young artists. In theory, this process isn’t problematic for anyone. How could it be? Listeners get entertaining songs, trap emcees are endlessly sought after, and pop artists sell their music in droves. However, in reality, one person loses out: the hip-hop fundamentalist, and unfortunately, the predicament of the archetypal hip-hop fundamentalist is never easy to watch. It is illustrated best as Joe Budden screaming at Lil Yachty about hip-hop’s “future” and the “vision” that Yachty and other trappers need to have for it. The old-heads are the ones with bulging necks and reddened faces, unable to change with the times and mercilessly questioning the legitimacy of the up-and-comers. Everyone else in the world is characterized by Yachty’s nonchalant response: “my n*gga… chill! I’m just making music bro, I’m just having fun!” Though, to rap’s avid curators and historians, that’s not what the genre should be, simply because it has the capacity to be so much more. A version of hip-hop that is “just fun” is hard to imagine when you grew up on the timeless stories of Slim Shady LP and The College Dropout. The thing is, no one seems to remember that in the early 1980s, that is exactly why hip-hop was created in first place: to use dope beats and inventive lyricism to have fun in a positive and expressive way. So if you identify as a self-proclaimed old head and don’t like where the new guys are taking the music, stop considering trap as the bastard child of modern hip-hop. Rather, think of it more as a return to hip-hop’s roots, but with more emphasis on monosyllabic ad-libs and red braids.

So, to address the central issue, yes – trap music definitely is being used as a means to an end. But it’s because people in all corners of the industry notice the intrinsic value that trap holds as music that everyone can enjoy, and according to the music’s creators, it was designed that way. It’s not a coincidence that Maroon 5 gave up on real rock years ago and now, years later, recruits Future to boost both their chart success and waning relevance. The same thing goes for Katy Perry. Haven’t released music in four years and looking for a cheap new rebranding? No worries – the path back to the limelight is paved with blonde pixie cuts and Migos features. Is it such a bad thing though? Maybe trap, both as a hip-hop subgenre and pop industry tool, is saving hip-hop from itself in the same way that if he’s not careful, Jack will become dull a boy from working too hard, but more importantly, could probably profit more than he ever has by just chilling out a bit. However, one caveat: whether you’re a trapper or pop singer, old head or new guy, one thing is for certain – if you’re going to engage at all with trap, at least try not to take its sound, image, and cultural relevance for granted; make sure to understand why these artists make music in the way that they do. And please, for the love of God, learn how to dance to it too.